Sell Amazon? Sell Tesla? One Analyst Just Made the Call Most Won't Make for Months.

Early morning. The city still waking, streetlights flickering off as dawn spreads across concrete. I walk past a newsstand—the kind that still exists in certain neighborhoods, stacked with newspapers and financial magazines that feel almost nostalgic in a digital age.

The headlines catch my eye.

"AI Boom Reshapes Markets."

"Tech Giants Face New Competition."

"Investors Rotate Into Small-Cap Innovators."

I pause, not because the stories are wrong, but because I've read these narratives before. Not in newspapers—in specialist forums, analyst notes, and research reports circulating months earlier among those who pay attention to signals rather than headlines.

The newsstand represents something I've observed throughout my career: mainstream media doesn't break financial stories. It confirms them. By the time a thesis reaches the front page, the earliest movers have already positioned, the analysts have already published, and the opportunity has already begun compressing.

The crowd always arrives late. Not because they're unintelligent, but because the infrastructure of information ensures delay.

The Nature of Lagging Narratives

Economic stories reach the public only after insiders have already acted. This isn't conspiracy—it's structure.

Consider 2008. The cracks in housing appeared in specialist reports throughout 2006 and 2007—rising delinquencies, deteriorating loan quality, synthetic CDO exposure that made risk managers nervous. A handful of analysts raised alarms. A few funds positioned short. But CNBC wasn't running crisis coverage until Bear Stearns collapsed.

By the time the public understood what was happening, the trade was over. Those who recognized early signals captured asymmetric returns. Those who waited for confirmation bought protection at the top.

The same pattern repeated with AI. Companies like NVIDIA were building the infrastructure for machine learning years before "AI boom" became a media phrase. Early investors who understood the computational demands of neural networks positioned quietly. The mainstream discovered the thesis after the stock had already moved hundreds of percent.

This is the nature of lagging narratives: the public learns about opportunity at the moment it transitions from asymmetric to efficient.

Signals Before Headlines

Some analysts build careers around spotting these signals early—identifying the dislocations before Bloomberg catches up.

Eric released his controversial "Sell This, Buy That" broadcast just days ago—making bold calls on selling Amazon and Tesla while revealing two alternative "BUY" recommendations he says are positioned like early-stage Amazon and the next big robotics winner.

I mention this not as endorsement of any specific position, but as example of the pattern: while mainstream coverage celebrates familiar giants, some observers are already rotating toward what they believe will be tomorrow's leaders. Whether their analysis proves correct is unknown. But the willingness to question consensus—to act before confirmation—is what separates early signal recognition from reactive positioning.

Eric released his controversial "Sell This, Buy That" broadcast just days ago.

In it, he made some surprising calls.

First, "Sell Amazon (AMZN)."

The morning after Eric went public with this recommendation, Bloomberg echoed Eric's doubts in an email saying money that would have normally been spent on Amazon.com is now going elsewhere.

But in a bit of one upmanship with Bloomberg, Eric took it even further by giving away an alternative "BUY" recommendation to all his viewers.

Watch right here to get the name and ticker of that little-known ecommerce stock - one he says is "more like buying Amazon stock in 2005."

On the same day, Bloomberg printed a headline nearly identical to Eric's rationale for his "Sell Tesla" call.

Bloomberg said Tesla's "remarkably patient investors now exist almost entirely on a diet of wild promises."

But Eric, once again, does better than the mainstream media - giving his viewers an exciting alternative to Tesla stock right here.

It's a company that's already amassing billions in cash from its robotics business and is well-positioned to leave Tesla's Optimus in the dust.

Look, if Eric is this far ahead of the game on Tesla and Amazon... we all better watch out for what the pundits are going to be saying about Nvidia soon.

That's right... Eric does NOT have good news on Nvidia in this video.

He does, however, have a very promising alternative stock pick.

It's a company whose AI hardware is scaling so rapidly that there is enough of it to circle the globe up to 8 times – in a single data center!

Yet it's barely making any headlines - yet.

You can get all the details on that company now in Eric's brand new "Sell This, Buy That" presentation.

But please, watch it now while Eric's "Buy" recommendations are still under-the-radar.

Use this opportunity to upgrade the stocks in your portfolio before it's too late.

What Early Really Looks Like

Here's what nobody tells you about acting early: it feels uncomfortable.

Early signs are fragile. They don't arrive with certainty. They arrive as whispers—data points that could be noise, thesis fragments that might not cohere, observations that contradict the prevailing narrative.

Early moves often contradict headlines. When CNBC celebrates a stock, buying something else feels contrarian to the point of recklessness. When everyone agrees that a company is unstoppable, suggesting rotation feels like heresy.

Early conviction looks reckless until it looks brilliant. The investors who bought Nvidia in 2016 weren't geniuses at the time—they were "betting on gaming chips" while serious money went elsewhere. The investors who bought Amazon in 2002 weren't visionaries—they were "catching a falling knife" after the dot-com collapse.

The emotional difficulty of early positioning is real. You act without confirmation. You hold without validation. And you wait—sometimes years—before the thesis becomes obvious to everyone else.

The Three-Layer Delay

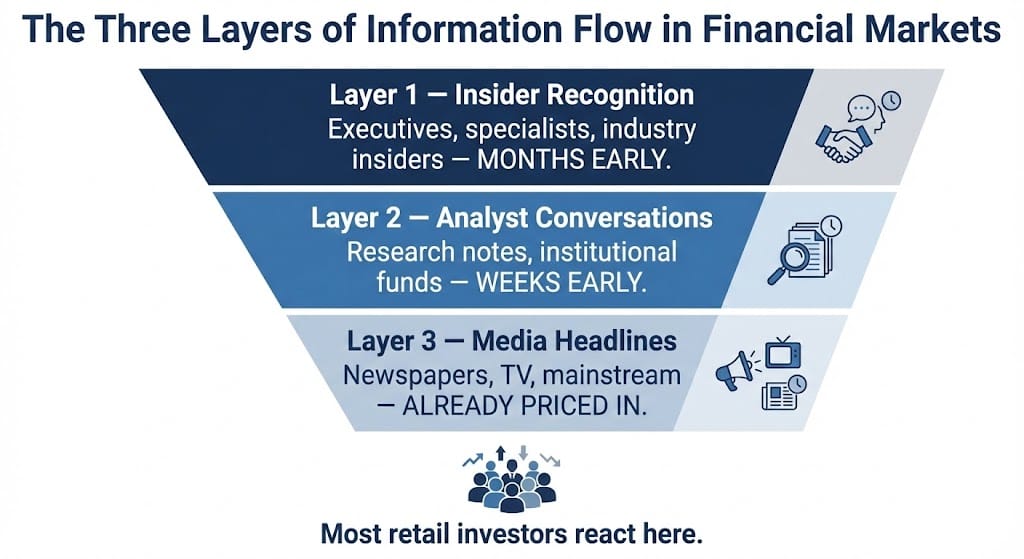

I think of information flow as operating through three layers:

Layer 1 — Insider Recognition: Company executives, specialized analysts, and industry participants recognize shifts first. They see the order books, the pipeline changes, the competitive dynamics before any report is published.

Layer 2 — Analyst Conversations: Research notes circulate among institutional investors. Hedge funds adjust positions. The thesis begins appearing in specialist publications and private forums.

Layer 3 — Media Headlines: Newspapers, television, and mainstream financial websites report the story. By now, it's consensus. The early positioning is complete.

Retail investors often react only at Layer 3. They buy after the headline, sell after the panic, and wonder why their returns lag the market. The delay isn't their fault—it's the structure of how information flows. But recognizing this structure is the first step toward positioning earlier.

False Certainty in Big Names

Why do investors cling to Amazon, Tesla, Nvidia—even when signals suggest rotation?

Comfort. These names are familiar. They've delivered returns. They appear in every portfolio, every index, every headline. Owning them feels safe.

Brand. Great companies become synonymous with their categories. Amazon is e-commerce. Tesla is electric vehicles. Nvidia is AI. The brand overshadows the business fundamentals.

Familiarity. Researching alternatives requires effort. Understanding new companies demands time. Sticking with what you know is easier than evaluating what you don't.

But comfort isn't strategy. The companies that dominate one era rarely dominate the next with the same intensity. Microsoft languished for a decade before its cloud renaissance. Intel dominated chips until it didn't. IBM defined computing until the PC revolution left it behind.

Clinging to giants because they were great is different from evaluating whether they will be great. And that evaluation requires confronting the discomfort of questioning consensus.

Rotation Is Not Betrayal

Here's the reframe I offer: reallocating capital from established giants into quieter innovators isn't speculation. It's intelligent positioning.

Rotation feels disloyal somehow—like abandoning companies that served your portfolio well. But investing isn't loyalty. It's capital allocation based on forward-looking analysis.

People dismiss alternatives because they're unfamiliar. A robotics company you've never heard of feels riskier than Tesla, even if the risk-reward calculus suggests otherwise. An emerging platform sounds speculative compared to Amazon, even if Amazon's growth has structurally slowed.

The discomfort of unfamiliarity protects incumbents long after their dominance has peaked. Recognizing this bias is the first step toward overcoming it.

When the Underdogs Became Titans

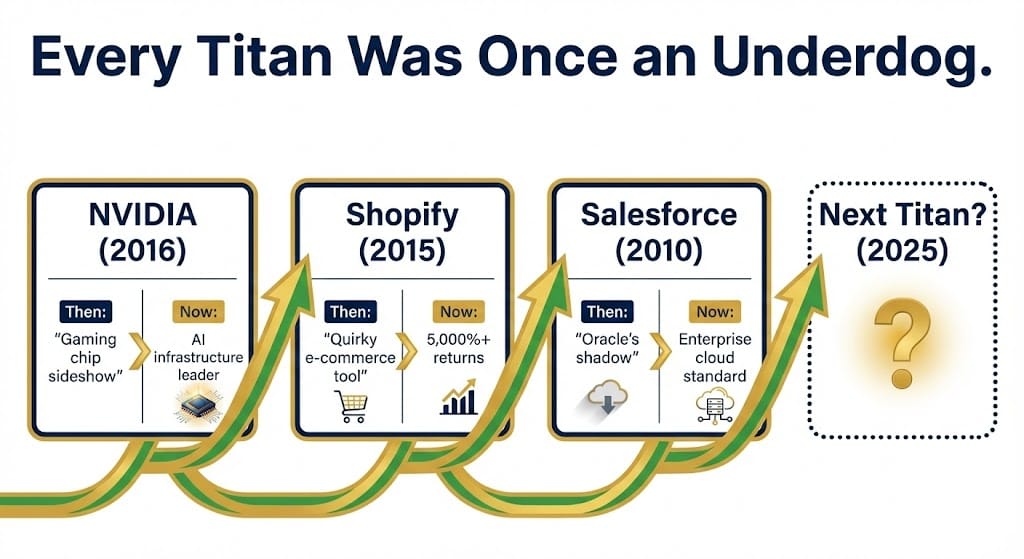

Every titan was once an underdog.

Nvidia was a gaming-chip company dismissed by serious investors focused on Intel and AMD . Then AI arrived, and the "gaming sideshow" became the most important semiconductor company in the world.

Shopify was a quirky e-commerce tool for small businesses while analysts obsessed over Amazon's dominance. Then millions of entrepreneurs built stores on its platform, and the stock appreciated over 5,000%.

Salesforce was ignored for nearly a decade—an enterprise software company in the shadow of Oracle and SAP . Then cloud computing became standard, and Salesforce became the default.

The pattern is consistent: the companies that define tomorrow's market are often invisible in today's headlines. They're discussed in Layer 1 conversations, analyzed in Layer 2 research, and finally celebrated in Layer 3 coverage—years after the early positioning window has closed.

The Cost of Ignoring Early Warnings

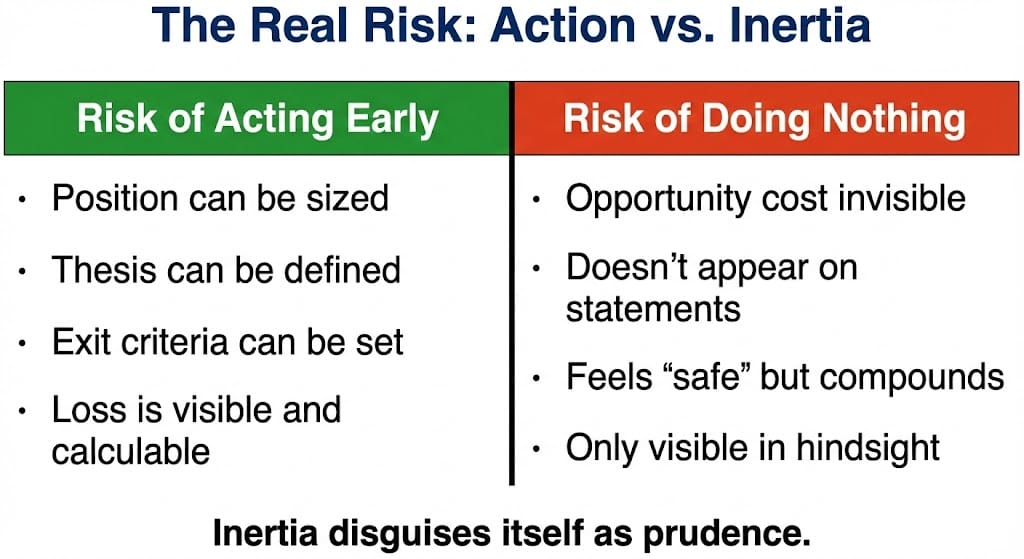

Investors lose the most not from risk-taking, but from inertia.

The risk of buying an unfamiliar company is calculable—you can size the position, define the thesis, set the exit criteria. The risk of doing nothing is invisible—opportunity cost doesn't appear on statements, doesn't trigger alerts, doesn't feel like loss until you calculate what could have been.

Inertia disguises itself as prudence. Staying in familiar names feels conservative. Avoiding new research feels like discipline. But when the familiar names stagnate and the unfamiliar names compound, the cost of comfort becomes staggering.

Grab 7 free trade ideas from futurist Eric Fry, including three little-known alternatives to Nvidia, Amazon and Tesla that could potentially double your money in 12-24 months.

InvestorPlace Media

I return to the newsstand in my mind—the headlines still screaming stories that analysts discussed months ago.

The crowd will always arrive late. The infrastructure of information ensures it. The psychology of comfort reinforces it. And the media's need for consensus narratives cements it.

But you don't have to be the crowd. You can choose to recognize signals at Layer 1 and Layer 2, to tolerate the discomfort of acting without confirmation, to rotate when the thesis supports it rather than when the headline validates it.

The outsized gains are claimed in the moment before the moment—when the opportunity still looks uncertain, when the names are still unfamiliar, when acting requires conviction rather than consensus.

By the time something becomes a headline, the early window has closed. What remains is efficient, priced, and available to everyone.

—

Claire West