The Asymmetry in Gold

There is a quiet moment every investor has experienced: watching a large, stable company trade sideways while the market waits for permission to be surprised. This is not boredom. This is mathematics.

Newmont trades at a price that reflects what it is — the world's largest gold producer, stable cash flows, a safe holding. But it trades at a price that constrains what it can become. A ten-billion-dollar market capitalization can grow, but only proportionally. It has already priced in competence, scale, and most reasonable scenarios. There is no room left for asymmetry.

This is why serious investors have learned to look elsewhere. Not for speculation. For structure.

The Buffett Illusion

Warren Buffett's framework — buy quality companies at reasonable prices, hold forever — works magnificently for capital preservation. It is the foundation of generational wealth for people who have time and discipline. But it is not a framework for outsized growth in mature asset classes.

Here is why: Newmont is priced for perfection that it cannot exceed. The company is the best-run large gold producer. Its AISC (all-in sustaining costs) improved to $1,593 per ounce in Q2 2025, below the industry median of $1,680. Its margin at current gold prices near $4,000/oz is approximately $2,400 per ounce — extraordinary by historical standards.

Yet the stock reflects this excellence already. When a company is large enough that the market trusts it completely, that trust becomes a price ceiling, not a floor. Newmont cannot surprise you upward. It can only disappoint you downward or deliver exactly what the market expects, which compounds at a boring rate.

The mathematics of compounding tells you: large safe companies become smaller safe companies relative to the broader market over time. This is not failure. It is gravity.

If Warren Buffett buys a gold stock, it will be Newmont (NEM).

The math is undeniable:

- Record Cash Flow: Newmont generated $4.5 billion in free cash flow year-to-date.

- Zero Debt: They’ve retired billions in notes to reach a near-zero net debt position.

- Deep Value: It trades at just ~11x earnings while gushing cash.

It is the only miner big enough to move the needle for Berkshire Hathaway.

But I am NOT recommending you buy Newmont.

Why? Because Newmont is already a giant. A 50% gain would be a miracle.

I am targeting the small, agile miners that Newmont (and its peers) will be forced to buy to keep their pipelines full.

These are the "100-bagger" candidates. The ones sitting on trophy assets with grades 13x higher than the industry average.

Get the names of the "Top 4" miners that could outperform Newmont 10-to-1.

Why Majors Can't Stand Still

But here is what you must understand: Newmont is not standing still. It is running uphill.

The company's own guidance reveals the problem: Cadia gold production will fall 40 percent in 2025 due to declining ore grades. Boddington and Tanami are following similar patterns — lower grades requiring planned mining sequences that depress near-term output to access higher-grade ore bodies deeper in the pit. Lihir, the company's critical Pacific asset, is in open-pit reconfiguration to stabilize production — a euphemism for managing declining grades.

This is the structural reality of large hard-rock mining. Once you extract the highest-grade ore, you must dig deeper for lower-grade material. Your fixed costs (the minehead, the processing mill, the administrative overhead) remain constant while your ore tonnage declines. Your cost per ounce rises. Your margins compress.

For a company like Newmont producing 5.6 million ounces annually, small grade declines mean enormous production challenges. For Cadia specifically, dropping from a certain grade to lower grades while transitioning to underground caving methods creates a production cliff that takes years to climb out of.

The majors know this. They are not blind to reserve depletion. They do not hope that grades will remain constant. They plan for replacement. And the only way to replace depleting reserves is to acquire them from smaller companies.

This is not a choice. This is a mathematical necessity.

Grades Matter More Than Headlines

Investors often hear the phrase "high-grade deposit" and think of it as marketing language. It is not. Grade is everything.

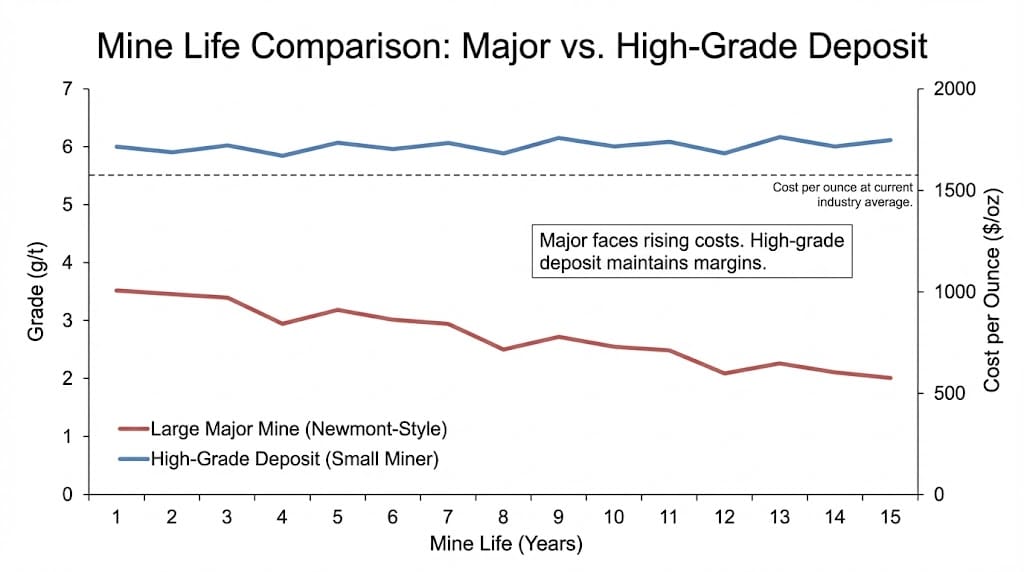

The World Gold Council defines ore grade in simple terms: below 5 grams per ton is low-grade (what most open-pit mines produce); 5-8 g/t is average; 8+ g/t is high-grade. The economic difference is not linear. It is exponential.

A one-gram-per-ton decrease in ore grade increases processing costs by approximately $50 per ounce. That means a deposit at 3.0 g/t costs roughly $300 per ounce more to process than a 5.0 g/t deposit at the same mine site, using the same infrastructure. This is why high-grade deposits remain economically resilient even when commodity prices fall — they have a structural cost advantage that survives market cycles.

Newmont's problem in 2025 is not that gold prices fell. Gold prices are near all-time highs. Newmont's problem is that its average grades are declining. The company is processing more rock to extract fewer ounces. Fixed costs are spread across lower production. Margins per ounce decline despite higher headline prices.

This is where the asymmetry emerges: smaller miners with high-grade deposits do not face this problem. A junior miner operating a 6.0 g/t deposit with a simple open-pit mine and a portable mill can generate astounding margins at current gold prices. A major miner processing 2.0 g/t ore with legacy infrastructure must fight for every percentage point of cost reduction.

When gold prices rise, high-grade deposits become not just profitable — they become target-worthy.

The Takeover Dynamic

This is the heart of mining M&A: majors do not acquire smaller companies because they have good management or compelling stories. They acquire them because they have something the major does not — assets with reserve lives long enough to support production for decades, and grades high enough to remain economical through commodity cycles.

In 2024, the gold M&A market saw $26.54 billion in deals across 62 transactions — more deals than 2023, but with lower average deal value. The largest transactions were strategic: De Grey Mining acquired by Northern Star Resources for $3.26 billion, AngloGold Ashanti acquiring Centamin for $2.48 billion, Gold Fields buying Osisko Mining for $1.42 billion.

What did these deals have in common? They targeted producing or near-producing assets with identifiable ore bodies, not startups or early-stage exploration plays. The majors paid premiums not for innovation or potential, but for certainty — known quantities of ore in the ground, with defined grades and mine plans.

Newmont itself has followed this pattern consistently. The Newcrest acquisition in 2023 for $17.8 billion brought reserve replacement and geographic diversification, but more importantly, it brought years of production from known assets without additional exploration risk.

This is the dynamic that remains consistently misunderstood: majors do not want to discover gold. They want to buy gold. Acquisition prices spike because majors are forced to bid aggressively for the limited pool of advanced assets that can replace their depleting reserves. Smaller miners with high-grade deposits become acquisition targets not when they are lucky, but when they are mathematically necessary.

Large-Cap Stability vs. Small-Cap Asymmetry

| Factor | Large-Cap (Newmont-Style) | Small-Cap (High-Grade Asset) |

|---|---|---|

| Market Cap | $55-70B | $500M-$3B |

| Upside Potential | 20-40% over multi-year cycle | 100%+ in acquisition scenario |

| Reserve Depletion Risk | Structural (grades declining) | Minimal (early mine life) |

| Ore Grade Profile | 2.0-3.5 g/t (declining) | 5.0-7.0 g/t (stable) |

| Cost Per Ounce | $1,593-$1,800 (under pressure) | $800-$1,100 (resilient) |

| Dividend Risk | Moderate (price-dependent) | Low (typically none paid) |

| M&A Target Risk | Acquirer (too large) | Target (strategic fit) |

| Buyer Behavior | Nobody wants to buy (antitrust) | Majors actively bidding |

| Cycle Role | Beneficiary of high prices | Beneficiary of high prices + M&A premium |

| Capital Intensity | Very high (sustaining billions annually) | Lower (operating existing asset) |

| Production Growth | 0-2% annually (challenged by grades) | Potential for ramp-up as mine develops |

Why This Cycle Is Different

Gold ended 2025 at record levels, with 53 all-time price highs achieved through the year. Central banks are buying gold at record pace, de-dollarization is accelerating, and geopolitical uncertainty remains elevated. Analysts suggest gold could reach $5,000 per ounce by 2030.

But here is the distinction: higher gold prices do not solve grade depletion. They make it worse. When gold prices are high, the majors become even more constrained in their strategic options. They cannot reinvest high cash flows into exploration and discovery — that takes 10-15 years to generate new reserves. They must acquire proven assets now. The urgency intensifies. The competition for assets increases. The premiums rise.

Political pressure on domestic mining in traditional centers (Australia, Canada, the U.S.) is simultaneously rising. Environmental permitting is tightening. Social license is harder to maintain. Majors are increasingly unable to develop new districts or expand existing operations without years of community engagement and regulatory battles.

For smaller miners holding advanced, high-grade projects in favorable jurisdictions, this creates a unique window. Majors need them more. Political risk is lower than for the majors' existing large operations. Regulatory approval timelines are shorter. The acquisition case becomes not just attractive — it becomes urgent.

Capital discipline by majors — a stated priority for Newmont and Barrick — means that organic expansion is off the table. M&A is the path to reserve replacement. And the only assets available at scale are the smaller miners holding them.

Capital Moves Slowly Until It Moves Fast

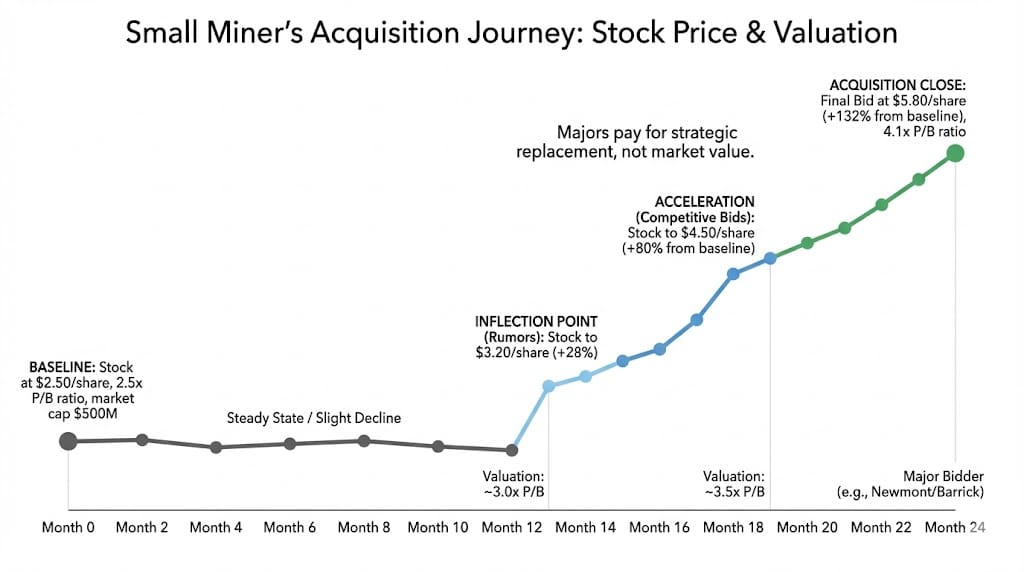

The final insight is this: mining M&A does not move linearly. For years, the market ignores smaller miners entirely. They trade on exploration results, funding rounds, and the whims of retail investors chasing gold narrative. The market does not price in acquisition probability. It prices in execution risk, financing risk, and timeline risk — which is why they trade at 2-3x cash flow multiples while majors trade at 15-20x earnings.

Then, over 12-18 months, everything changes. A major becomes serious. Due diligence begins. Competitive bids emerge. The asset is suddenly valued not for its ongoing operating cash flow, but for its strategic replacement value to a Fortune 500 company desperate to maintain production.

The re-rating happens overnight. Not because the asset changed. Because the buyer's situation changed.

This is how wealth is actually made in commodity cycles — not through clever speculation or timing the gold price to the day. But through understanding which assets majors are structurally forced to acquire, and positioning accordingly while the market still prices them as small explorers.

Patience is a strategy. Understanding capital flows is an edge. And sometimes, the most profitable move in a gold cycle is the one that looks boring until it doesn't.

—

Claire West