The Balance Sheet That Rewires Systems

A number appears on the Federal Reserve's balance sheet every quarter. It is not dramatic. It does not generate headlines. It simply states: the value of gold held in reserve. In April 2025, that number increased by €130 billion. In July, it declined by €29.7 billion. The gold itself did not move. The price changed. The accounting updated. And billions of euros of purchasing power shifted on the central bank's balance sheet without a single announcement.

This is how monetary systems actually work. Not through dramatic policy shifts or political announcements, but through quiet accounting changes that, over time, rewire the structure of how value flows.

Most people think gold's relevance ended when the world abandoned the gold standard in 1971. This is almost entirely wrong. Gold never disappeared from monetary systems. It was simply frozen in place—held on balance sheets at prices frozen in 1973, while the world moved on. The value gap between what gold actually costs ($3,300+ per ounce in 2025) and what it officially costs ($42.22 per ounce on U.S. Treasury books) has widened into an absurdity.

This gap is not accident. It is contingency planning.

Gold's Strange Status: Everywhere and Officially Ignored

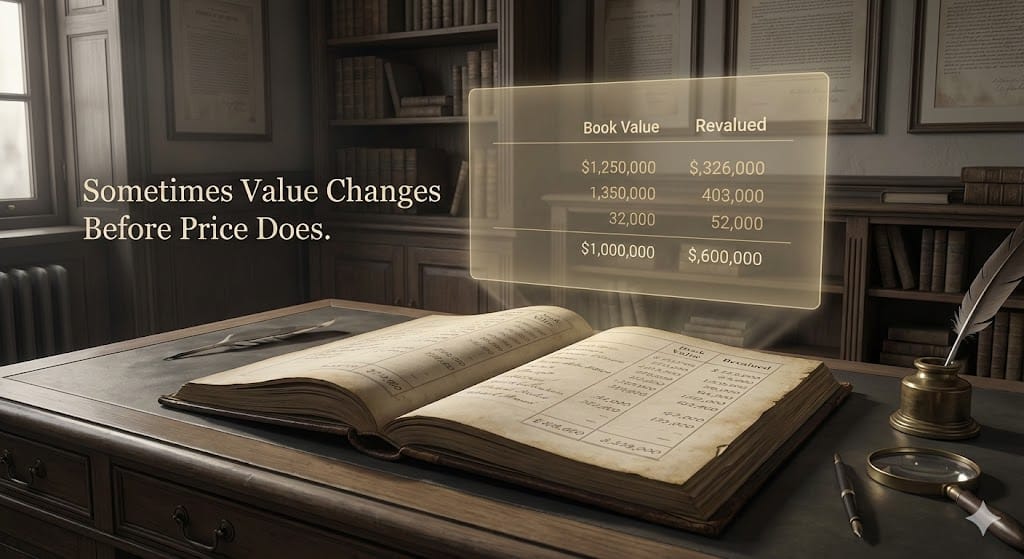

The U.S. Treasury holds 261 million ounces of gold. At market prices, this is worth approximately $860 billion. On official balance sheets, it is worth $11 billion. The difference—roughly $849 billion—sits in an unrealized revaluation account, available but not recognized.

Central banks globally hold approximately 33,000 metric tonnes of gold, valued at roughly $1.4 trillion at market prices. Yet most central bank balance sheets report this gold at values disconnected from market reality. The European Central Bank revalues quarterly, marking gold to market. The U.S. Treasury does not, maintaining decades-old statutory valuations.

This is not negligence. It is intentional design. The Gold Reserve Act of 1934 established the structure: the Federal Reserve transferred all its gold to the Treasury, received gold certificates in exchange, and the Treasury gained the power to establish gold's official price. That power—dormant since 1973—remains intact.

Why would a government maintain an accounting system that so dramatically understates an asset's value? Because the moment the government revalues that asset upward, it signals something to markets: the currency might be weaker than previously acknowledged. The balance sheet structure itself contains information.

Donald Trump Jr. just urged Americans to take action now! He says, “My father's administration is exploring a powerful economic tool that…”

Read his full message here

Marketing as Probability, Not Persuasion

Most people conflate gold's market price with its monetary status. They are different things.

Gold's price in dollars has risen from $35 per ounce (1944-1971) to $42.22 (1973-2025) to $3,300+ (2025). This 8,000 percent nominal increase is not primarily because gold became scarcer or more valuable. It is because the dollar became weaker.

A single ounce of gold, measured in purchasing power, has remained relatively stable. In ancient Rome, one ounce bought a quality toga and sandals. In 1920, it bought a men's suit. In 2025, it buys a men's suit. The value did not change. The currency changed.

This distinction—price versus recognition—is the critical insight. A government revaluation of gold would not make gold more valuable. It would make gold's monetary status formally recognized again.

Currently, gold is both everywhere and nowhere in the system. Central banks hold it as their largest reserve asset. The IMF tracks "monetary gold" held by approximately 100 central banks. Yet gold plays no official role in modern monetary architecture. It is a ghost in the machine.

A revaluation would change this. Not by making gold more valuable, but by formally acknowledging that gold should anchor the system—at least partially, at least again.

Why This Matters Systemically

Consider the arithmetic. The U.S. debt stands at $38 trillion. Annual interest costs have risen to $1.21 trillion. Foreign buyers of Treasury securities are retreating. The government faces increasing pressure to either reduce spending (politically toxic), raise interest rates to attract buyers (economically painful), or create new monetary sources.

A gold revaluation would accomplish the third option without creating new physical assets or directly increasing nominal debt. Here is how:

Congress approves a new statutory gold price. The Treasury issues new gold certificates to the Federal Reserve at this higher price. The Fed's balance sheet increases—it now holds higher-value gold certificates. The Treasury's account at the Fed increases correspondingly. The Treasury can then spend this "new money" without issuing new debt.

A $500 billion revaluation would inject $500 billion into the system. This is equivalent to quantitative easing—monetary expansion—but accomplished through asset revaluation rather than debt purchase.

Why would a government consider this? Because the balance sheet math shows gold as absurdly undervalued relative to what the government actually owes. Revaluing the asset brings the balance sheet into better alignment with economic reality.

Historical Pattern: Revaluations Precede Regime Shifts

Revaluations happen not during normal times, but during transitions. The 1934 Gold Reserve Act transferred gold from the Federal Reserve to the Treasury as the world moved away from the classical gold standard. The 1972-1973 revaluations (raising the official price from $35 to $42.22) occurred as the Bretton Woods system collapsed.

In each case, the revaluation happened quietly. No dramatic announcement. Technical changes to law. Gradual price adjustments. By the time markets fully recognized what had occurred, the regime had already shifted.

The Federal Reserve is currently publishing technical research on revaluation mechanics. The Treasury is exploring a "sovereign wealth fund" that would monetize government assets. Hedge funds are positioning for potential gold revaluation. Belgium is floating the idea of monetizing central bank gold for fiscal spending.

These are not coincidental discussions. They are contingency planning that precedes formal policy by months or years.

Paper Assets vs. Monetary Anchors

| Dimension | Paper Assets | Monetary Anchors |

|---|---|---|

| Counterparty Risk | High (depends on issuer) | None (gold is final settlement) |

| Policy Vulnerability | High (can be devalued, frozen, seized) | Low (government controls value, not creation) |

| Crisis Reliability | Questionable (frozen during stress) | Proven (remains liquid even in turmoil) |

| Geopolitical Neutrality | No (currency blocs, sanctions exposure) | Yes (recognized everywhere) |

| Purchasing Power | Declining (inflation) | Stable (over centuries) |

| Balance Sheet Transparency | Varies (accounting changes, valuations drift) | Fixed (market price clear) |

| Confidence Requirement | High (belief in issuer) | Low (physical reality) |

| Role in Regime Shifts | Depreciate (lose value) | Revalue (gain recognition) |

Gold's advantage is not that it makes you rich. It is that it anchors value independent of government promises. This becomes critical during monetary transitions, when paper assets lose credibility.

Why Governments Act Quietly

Imagine a headline: "U.S. Government Revalues Gold by 500%, Creating $500 Billion in New Money." The market reaction would be immediate. The dollar would weaken. Inflation expectations would spike. Foreign creditors would question the dollar's stability.

Now imagine the same policy implemented quietly: technical accounting changes, Treasury explores gold monetization, Federal Reserve publishes research. Markets absorb it gradually. The revaluation happens in quarters and years, not days. By the time the policy is obvious, it has already taken effect.

This is how all major monetary shifts happen. Not announced, but discovered. Not dramatic, but inevitable.

Recognition Before Valuation

The most important insight is that a gold revaluation is not really about gold. It is about recognition. The world's central banks are already buying gold at record pace, even at high prices. They understand something that official policy still ignores: gold serves a monetary function in the system, whether or not that function is formally acknowledged.

The value of gold at $3,300 per ounce is not speculative excess. Central banks accumulating at this price suggests they have recalibrated what gold is worth to the monetary system. They recognize something that official balance sheets have not yet acknowledged.

When—not if, but when—the Treasury revalues gold upward, it will not be creating value. It will be recognizing value that already exists, that central banks already understand, and that the market has already priced.

Balance Sheet Reality vs. Political Narrative

Monetary systems are understood through balance sheets, not speeches. A government can announce policies that never materialize. But when it begins changing the accounting—when central banks revalue quarterly, when the Treasury explores asset monetization, when the Federal Reserve publishes revaluation research—the system is already moving.

The gold on the Treasury's books at $42.22 per ounce will not remain there forever. The accounting contradiction is too obvious, the monetary pressure too great, the central bank behavior too clear. Revaluation is not a matter of if, but of timing and magnitude.

When it occurs, it will likely be described as routine. "Treasury modernizes gold accounting" or "Fed implements technical adjustments." Most observers will not understand what happened. But the balance sheet will have been rewired, the monetary system restructured, and the status of gold formally acknowledged.

This is how the most important financial changes actually occur: quietly, through accounting changes, recognized only in retrospect.

—

Claire West