The Energy Ceiling: Why AI's Next Constraint Isn't Chips or Code

There's a particular kind of silence that arrives when someone stops believing their own narrative and confronts what's actually happening.

I felt it recently, reading about Google's latest solar experiments—orbiting reflectors to beam concentrated sunlight down to terrestrial panels. On the surface, it's classic tech optimism: innovation, boldness, reimagining the possible.

But beneath that narrative is something else: desperation wrapped in research.

Google isn't launching orbital solar experiments because it's the obvious next frontier of renewable energy. It's launching them because traditional power scaling—the kind that's fed every technological revolution since electricity was invented—is no longer keeping pace with what the company needs.

Somewhere in that realization, a shift happened in how I think about AI's future. It's no longer a story about software, algorithms, or even chip design. It's a story about energy and the physical constraints that no amount of innovation can simply wish away.

The AI Illusion

For the past two years, the narrative around AI has been almost entirely focused on the computational layer: bigger models, faster chips, more NVIDIA GPUs, better architectures.

The implicit belief: if we can keep building chips faster, we can keep scaling AI models indefinitely.

But that belief rested on an unstated assumption: that energy would scale at the same pace as compute.

It hasn't. And it won't.

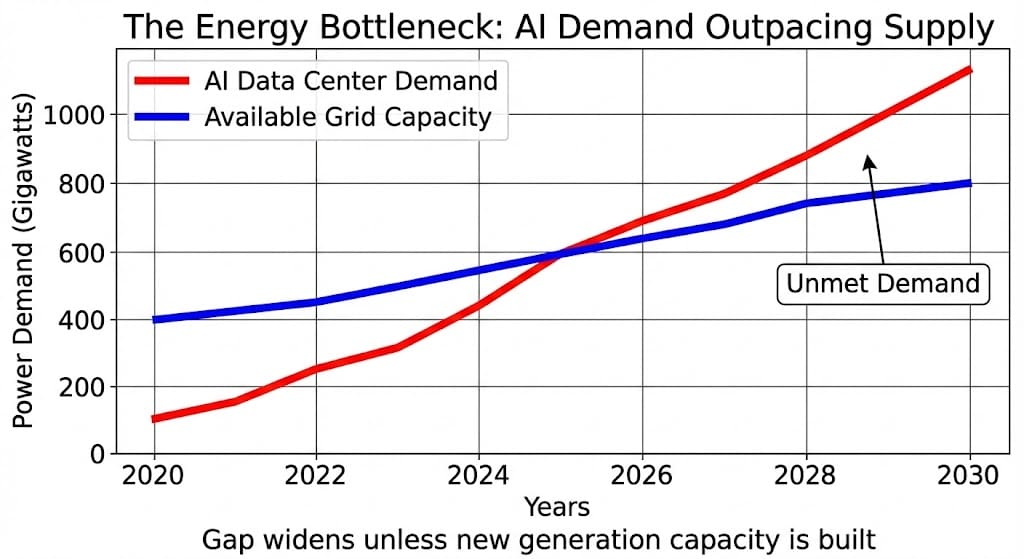

Data centers that used to draw megawatts now demand gigawatts. The power density of modern GPU clusters is approaching the thermal limits of what cooling systems can handle. The electricity required to train, run, and maintain state-of-the-art AI systems is no longer a line item in a budget—it's becoming the dominant cost structure.

And here's the uncomfortable part: electricity doesn't scale like software. You can't optimize it. You can't parallelize it. You can't wait for the next generation. You either have it, or you don't.

The AI boom wasn't built on unlimited compute. It was built on a few years of abundant, cheap electricity in regions with surplus power generation. That window is closing.

Google’s "Project Suncatcher" admits defeat: Earth’s grid can’t power AI.While Google flees to orbit for 8x solar efficiency, Microsoft is restarting Three Mile Island to secure terrestrial power.

The race is on. Trump’s Executive Order 14301 mandates new nuclear reactors by July 4, 2026.

But they all require one critical "AI Fuel" (HALEU).

One small company holds the key.

CLICK HERE: See The Name & Ticker Symbol Behind The $100 Trillion HALEU "AI Fuel" Monopoly

The Grid Constraint

The U.S. electrical grid is not designed for what's being asked of it.

Demand from AI data centers, combined with electrification of transportation and heating, is pushing grid capacity to limits that were never intended to be reached. Utilities are starting to face a choice they haven't had to make in decades: either invest hundreds of billions in new generation capacity, or admit they can't meet demand.

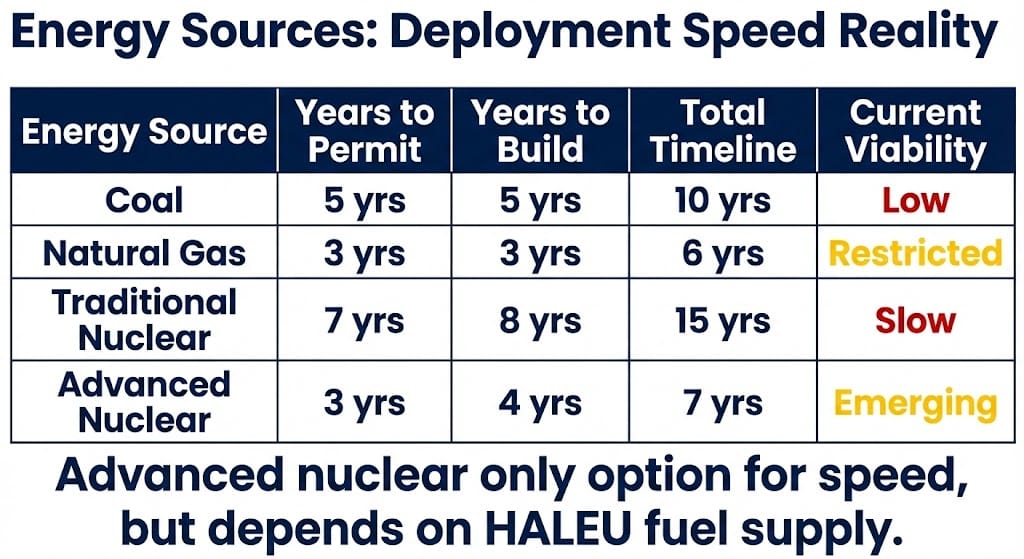

The traditional answer would be: build more coal plants or natural gas facilities. But politics, emissions goals, and simple timing make that untenable. Coal takes 10 years to permit and build. Natural gas is increasingly restricted. Renewables—wind and solar—are intermittent and require massive battery storage that doesn't yet exist at scale.

Which leaves nuclear as the only realistic option for dense, baseload power.

But nuclear plants take 15+ years to build, require enormous capital, and face political headwinds. So what do you do when you need power now, not in 2040?

You look for shortcuts. You restart old plants. You experiment with orbiting solar. You pivot to wherever power already exists.

This is what Google, Microsoft , and Amazon are doing right now. Not out of boldness or vision, but out of constraint.

Orbital vs. Terrestrial: What the Divergence Reveals

Google's orbital solar project and Microsoft's decision to restart dormant nuclear reactors tell opposite stories about the same problem.

Google is asking: "Can we create new power sources that don't depend on existing infrastructure?"

Microsoft is asking: "Can we use existing assets—neglected nuclear plants—to meet our immediate power needs?"

One is a long-term bet on technological breakthrough. The other is a pragmatic grab for what's available today.

Both reveal the same underlying reality: the existing grid cannot support AI at its current or projected scale. The question is no longer "How do we optimize?" It's "Where do we get power?"

This divergence matters because it shows how seriously these companies are taking the constraint. You don't restart nuclear reactors out of casual interest. You do it when you believe your business model depends on it.

Policy Acknowledgment: What the Executive Order Actually Admits

Executive orders about nuclear energy aren't usually the stuff of high drama. But President Trump's recent moves to accelerate nuclear licensing and permitting, combined with policy support for advanced reactor deployment, represent something significant: official acknowledgment that traditional energy infrastructure is insufficient.

When a president's executive order prioritizes nuclear acceleration, it's not really about nuclear policy. It's about admitting that without it, the AI economy hits a ceiling within years, not decades.

The policy doesn't solve the problem. It just tries to compress timelines. New reactor permits might come in 5-7 years instead of 15+. But even that assumes no significant delays, which is optimistic for nuclear projects.

What the policy actually reveals is desperation hidden behind the language of progress.

The Hidden Dependency: HALEU and Supply Constraints

Here's where the story gets more specific.

Advanced nuclear reactors—the kind that could theoretically be deployed faster than traditional plants—require a specialized fuel called High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium, or HALEU.

HALEU is different from traditional reactor fuel. It's more energy-dense, more efficient, more suited to compact designs. Which means advanced reactors can be built smaller, permitting faster, and deployed with less massive infrastructure.

The problem: HALEU has essentially no commercial supply chain in the United States. It's a specialized product. It's tightly controlled for non-proliferation reasons. And it's produced by only a handful of countries, most of which are not geopolitically aligned with the U.S.

Which means the deployment of advanced reactors—the theoretical solution to the energy constraint—depends on solving an upstream supply problem that hasn't been solved yet.

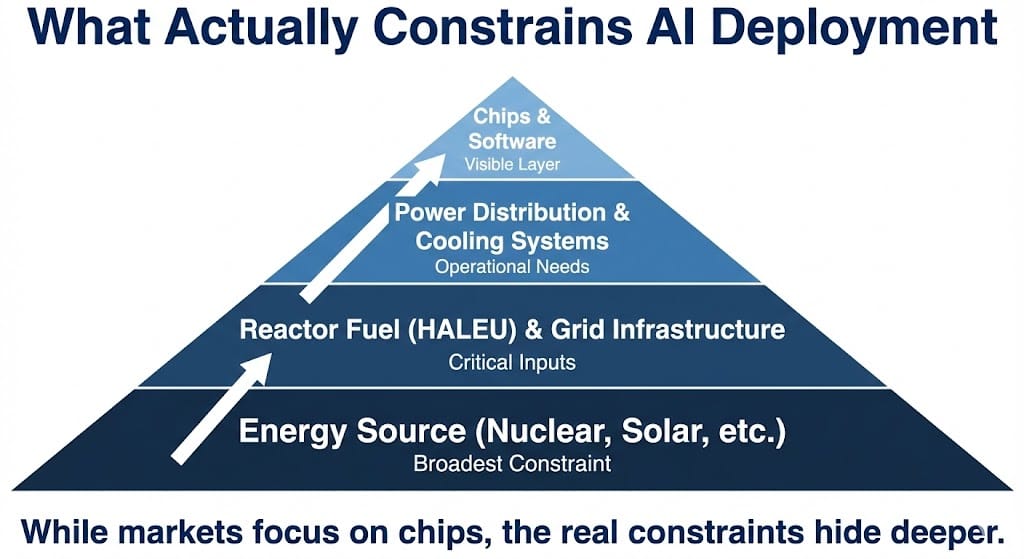

This is the hidden layer. While everyone discusses AI compute and chip design, a much quieter constraint is tightening: the fuel that powers the next generation of reactors.

Infrastructure vs. Innovation

Here's a framework that clarifies the distinction:

Innovation:

- Fast moving

- Software-like scaling

- Talent-driven

- Disrupts incumbents

Infrastructure:

- Slow moving

- Physics-constrained

- Capital-intensive

- Creates moats

For the past two decades, the tech industry has operated almost entirely in the Innovation layer. Speed, disruption, talent, and software dynamics.

But AI is forcing a shift to the Infrastructure layer. And in that layer, the old rules apply: speed is constrained by physics and permitting. Scaling requires capital and time. And control of inputs often matters more than control of outputs.

A company that owns the supply of HALEU has more durable competitive advantage than a company that owns the best algorithm. Because algorithms can be replicated. Supply chains can't—not quickly.

Why Markets Miss Input-Layer Leverage

Stock markets love platform stories. They love companies with network effects and software-like scaling.

What they struggle with is input-layer leverage—the quiet advantage of controlling a bottleneck upstream.

When HALEU was obscure, nobody priced it as valuable. When advanced reactors were theoretical, the fuel supply didn't matter. Now that both are becoming necessary, the market is slowly recognizing the constraint.

Advanced nuclear reactors require High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU), a specialized fuel with limited suppliers. One U.S.-linked company controls a critical portion of this supply chain, positioning it as an upstream beneficiary of AI-driven energy demand.

This isn't about predicting returns. It's about recognizing that physical constraints create durable value in unexpected places.

Why Inputs Often Outweigh Platforms

A platform can be disrupted. A supply chain can be replicated—eventually.

But a fundamental input—something required by the entire system—creates a different kind of advantage. It's less dramatic than disruption. It's less exciting than a breakthrough. But it's often more durable.

Oil companies didn't become powerful because they were innovative. They became powerful because every transportation system in the world required their product. The same dynamic is emerging around energy inputs for AI infrastructure.

Control the fuel, and you control the pace of deployment. Control the deployment timeline, and you influence which systems scale first and which lag. Control the first-mover advantage, and you shape the entire sector.

This is why mundane supply chains matter more than most investors realize.

AMERICA’S $100 TRILLION HEARTLAND REVIVAL

Brownstone Research

The AI boom has been a story of ideas outpacing infrastructure. Brilliant researchers publishing papers. Engineers building systems that seem to defy previous limitations. Companies making claims about what's possible.

But beneath that story is always a simpler truth: systems scale on physics, not narratives.

Energy density has hard limits. Grid capacity is finite. Supply chains take time to build. Nuclear fuel is specialized and scarce.

These constraints don't care about innovation or disruption or the brilliance of any individual researcher. They're just the friction between what we want to build and what the physical world allows.

The AI revolution will continue. But its pace and shape will be determined less by chip design than by kilowatt-hours available. Less by algorithm cleverness than by reactor deployment timelines. Less by software optimization than by uranium enrichment capacity.

In the end, every technological revolution has been constrained by its energy input. This one will be no different. The only question is whether the markets—and the investors making decisions based on them—recognize the constraint before it becomes obvious.

History suggests they won't.

—

Claire West