The Erosion Nobody Notices

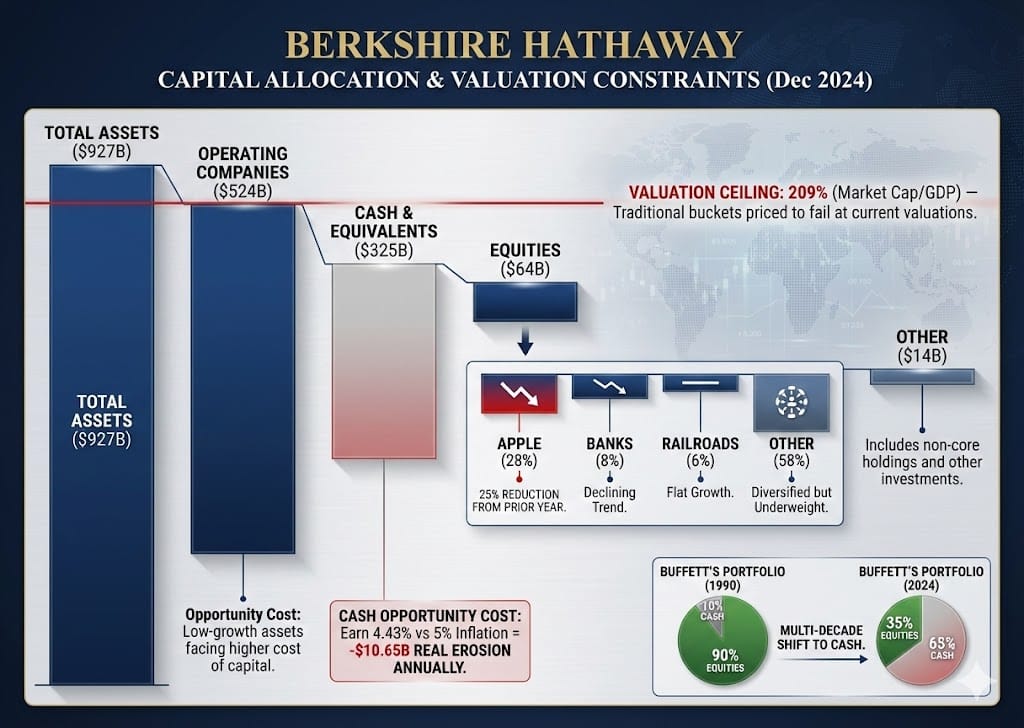

Warren Buffett is holding $325 billion in cash. Not deploying it. Not taking earnings from it. Just holding it, while inflation silently erodes its purchasing power at roughly 3.1 percent annually.

This is the paradox at the heart of modern capital management: the safest position—cash—is the most expensive position when inflation persists. A dollar today is worth 97 cents next year in purchasing power, even if the bank pays you 4 percent in return. At Berkshire's scale, this invisible tax costs roughly $10 billion annually in unrealized losses.

Buffett, famously, does not hold idle capital. He invests it. The fact that he is holding this much means something specific: his traditional investment buckets—banks, railroads, mega-cap technology—no longer offer sufficient margins of safety. The market's valuation, measured by his preferred metric (total stock market value divided by GDP), stands at 209 percent, a level not seen since 1929.

When valuations become this stretched and inflation becomes this persistent, traditional assets fail. And when traditional assets fail, capital must move somewhere. Not to protect against catastrophe, but to capture real, inflation-adjusted returns.

Gold mining—not the metal itself, but the business of extracting it—is where this capital is quietly beginning to move.

Why Cash Feels Safe But Isn't

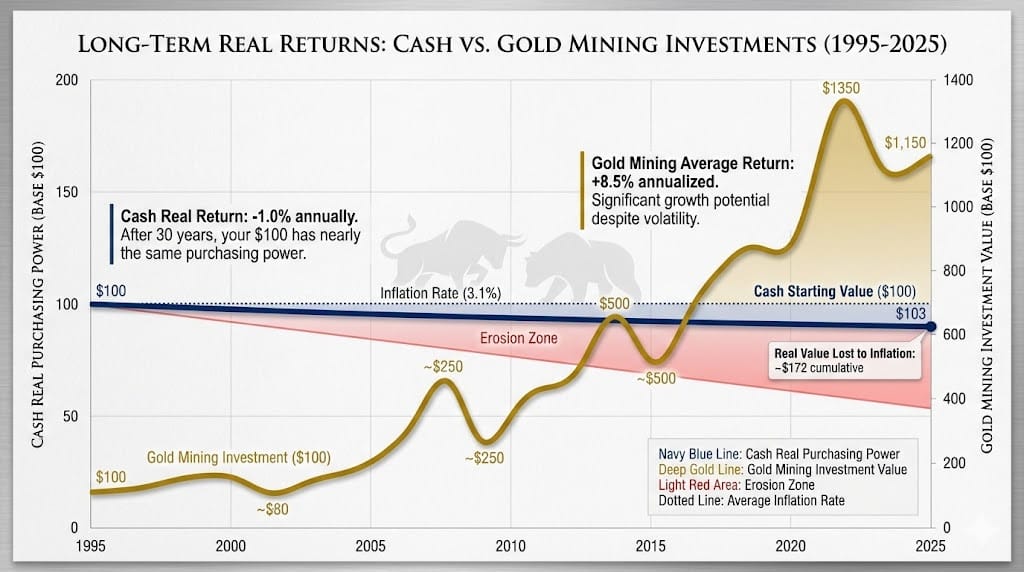

Cash is the psychological comfort position. It feels like you are avoiding risk. In reality, you are accepting a specific risk: the certainty of inflation erosion against the possibility of market volatility.

The mathematics is brutal. If cash earns 4 percent and inflation runs at 5 percent, you lose 1 percent in real purchasing power each year. Over decades, this compounds to catastrophic wealth destruction. A holder of £100 in cash 30 years ago—earning interest rates that were historically elevated—would have only £103 in real purchasing power today.

This is not a minor issue. It is the foundational problem with holding massive capital reserves during inflationary periods. Every month Buffett's $325 billion sits in Treasury bills earning 4.43 percent, it loses roughly $850 million in real value to inflation that exceeds those returns.

For individual investors, this might be acceptable—the psychological cost of a market drawdown might outweigh the hidden cost of inflation. But at institutional scale, this becomes operationally untenable. A $325 billion hoard is not a position of flexibility. It is a constraint. Capital this large cannot sit idle while the world restructures around it.

This is why Buffett sold $133 billion worth of equity in 2024—not out of panic, but out of necessity. The traditional assets were priced too high to warrant allocation of new capital. Yet the cash had to go somewhere. So it accumulated, waiting for opportunities that made sense.

Now, as the opportunity set shifts, the capital flows are beginning to follow.

A lot of investors write in to tell me how much they’ve made in Bitcoin. My reply? Good for you. First off, gold investing is cyclical. You really only want to own gold at one specific time in the cycle. That time is now. Second, the world’s governments are not buying Bitcoin. They’re betting on gold. All of them. Bitcoin (does anyone really know for sure the US government didn’t create it?) will be a good bet… until it isn’t. It may end up doing great. Or it may be eclipsed by any number of tech developments.

Meanwhile, gold will continue to do what it’s done for almost 6,000 years of recorded human history: Protect wealth through chaos.

Go here if you want the name and ticker of Buffett’s likely gold play… and details on my top four miners

Valuation Collapse in Traditional Buckets

For three decades, Buffett's portfolio rested on three pillars: financial institutions (banks), transportation (railroads), and stable mega-cap technology. These were the assets that combined durability, cash generation, and reasonable valuations. No longer.

Banks have been hollowed out as interest rate regimes become more volatile and regulatory constraints tighten. The railroad business remains intact but is mature, cyclical, and limited in growth. Even Apple, which Buffett held at 51 percent of his portfolio in 2023, he has reduced to 28 percent, with sales in every quarter of 2024.

Why Apple? Not because the company has deteriorated, but because valuations became unjustifiable even for a franchise of that quality. The price premium left insufficient margin of safety for capital of Berkshire's size and return requirements.

And the broader market is worse. The S&P 500 at current valuations requires either exceptional earnings growth or continued expansion of valuation multiples—neither of which has substantial margin for error. Buffett exited his entire position in S&P 500 ETFs in Q4 2024, a signal of profound skepticism about broad market valuations.

When these buckets fail—when the core assets you have relied on for three decades become unaffordable—capital simply has nowhere traditional to go. At that point, the investor must either hold cash and accept real erosion, or look for completely different asset classes.

Gold Mining: The Productive Alternative

This is where gold mining becomes not a speculation, but a rational allocation. Not because gold is a "fear trade" or a hedge against collapse. But because gold mining is fundamentally a cash-flow business—the inverse of speculative commodity holding.

Operating gold miners produce actual cash today. Agico Eagle's Q3 2025 production: 866,936 ounces at $963 per ounce in cash costs. At current gold prices exceeding $2,400 per ounce, this creates a $1,400+ per ounce operating margin. This is not theoretical. This is cash flow, realized quarterly, visible in financial statements.

Eldorado Gold increased reserves 5 percent despite production depletion, extended mine life to 13 years, and conservatively updated gold price assumptions to $1,700 per ounce (up from $1,450). Again, actual cash generation being added to the reserve base every quarter.

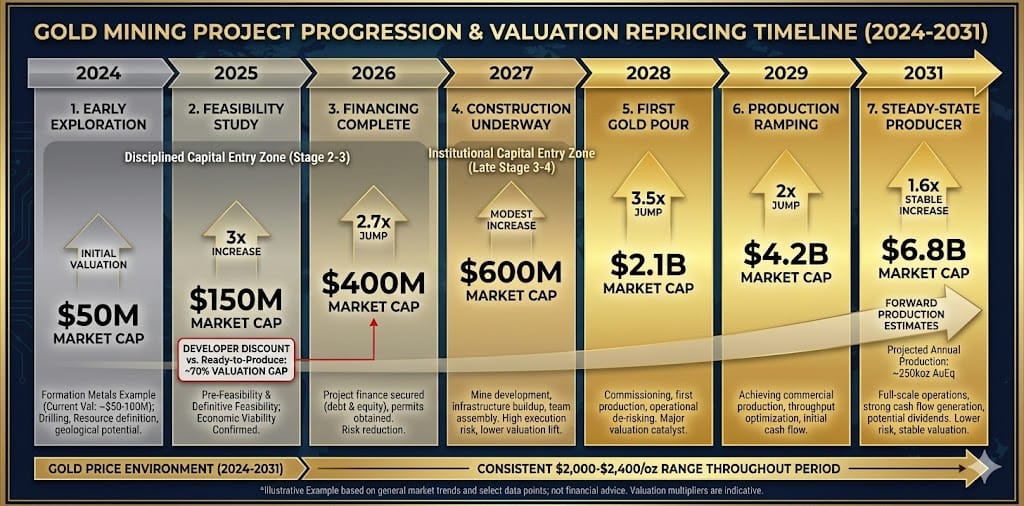

But the more interesting opportunity sits one level earlier in the cycle: developer companies approaching production. These are companies that have drilled the ore body, completed feasibility studies, received environmental approvals, and are now executing construction toward first production. Formation Metals, for instance, has a fully funded 30,000-meter drill program on its N2 Project, with C$13.5 million in working capital and zero debt.

Hecla Mining's Midas Project in Nevada requires capital restart, but the mill and tailings facility are already permitted and substantially empty—an existing infrastructure advantage that cuts capital requirements by 30-50 percent relative to greenfield development.

These are not speculative assets. They are disciplined progression toward cash generation, with visible timelines and capital requirements.

Why Developer Valuations Lag Production Readiness

The psychology of mining investment creates systematic mispricing. When gold prices rise, investors buy the operators—the companies already producing gold with the immediate earnings visibility. These get repriced rapidly and, by the time developers become obvious, the operators have already tripled.

But developers—those 3-5 years from production—price in far less certainty than they warrant. The market prices them as if production is unlikely, even when engineering studies prove it is probably certain. This creates a timeline-based repricing opportunity that institutional capital is only now beginning to recognize.

Early in 2025, developer companies with proven management teams (those who have successfully built and exited mines before) were still trading at substantial discounts to their probable production-ready valuations. By late 2025, as institutional interest increased, this gap began compressing.

For a capital deployer with Buffett's characteristics—massive scale, long time horizon, patient capital—developers approaching production offer precisely the opportunity his position requires: real cash-flow assets with inflation protection, trading at valuations that do not yet reflect production certainty.

Cycle Timing: When Gold Mining Matters

Gold mining does not work at all times. When gold prices are at historical lows ($300-500/oz), mining developers struggle to finance and produce value. Investors in gold miners during those periods often lose capital.

But gold mining creates extraordinary returns at specific moments: when gold prices have risen substantially, operating margins are visible and compounded into reserve values, yet developers approaching production have not yet been repriced by the broader market.

That moment is now. Gold prices are at historic highs (~$2,400+). Operating producers have already tripled or quadrupled. But developers still trade at valuations that do not reflect their 2-3 year timeline to production.

Within 3-5 years, assuming current gold prices hold at even $1,800+ per ounce, developers now approaching production will be generating billions in cash annually. The companies that financed them at current valuations will have compounded their capital substantially.

This is not prediction of gold price direction. This is recognition of cycle timing—the window when productive assets at scale make sense for large capital deployers.

Why Discipline Matters More Than Direction

The risk of this analysis is obvious: gold prices could fall. Mines could face construction delays. Environmental regulations could tighten. All real risks, and none to be dismissed.

But for a capital holder like Buffett facing $10 billion in annual real erosion from inflation, the risk of holding cash is certain. The risk of gold mining is probable but not certain. Allocating to probable risk beats accepting certain erosion.

This is the shift in thinking required when traditional asset classes become unaffordable. You are not trying to get rich. You are trying to preserve capital while remaining invested in productive assets.

Gold mining, at this phase of the cycle, with disciplined management teams and visible paths to production, offers that combination. Real cash flows from actual operations. Inflation protection. Valuations that have not yet reset to production readiness.

The allocation is not made out of conviction that gold will soar. It is made out of recognition that cash at current returns is mathematically losing, and that productive assets generating actual cash flows are available at valuations not yet reflecting their production status.

This is how capital actually moves at institutional scale: not in response to narratives, but in response to the mathematics of real returns becoming untenable.

Buffett's $325 billion in cash is not a bet on a market crash. It is a recognition that traditional assets are priced to fail, and that gold mining developers represent one of the few remaining asset classes where large capital can be deployed at valuations that offer real, inflation-adjusted returns.

Patience, as always, is the asset class itself.

—

Claire West