The Invisible Layers: Why Big Tech Buys What Looks Boring

There's a pattern in how technological systems actually develop, and it's almost entirely invisible because it's so unglamorous.

A company launches something novel. Everyone talks about it. It trends. Stock prices spike. Media declares it revolutionary.

Then, quietly, over years, the same company acquires a series of boring, Infrastructure-level businesses that most people have never heard of. These acquisitions barely make news. They're not the "sexy" moves that generate headlines.

But they're often the acquisitions that determine whether the original innovation actually scales into something durable.

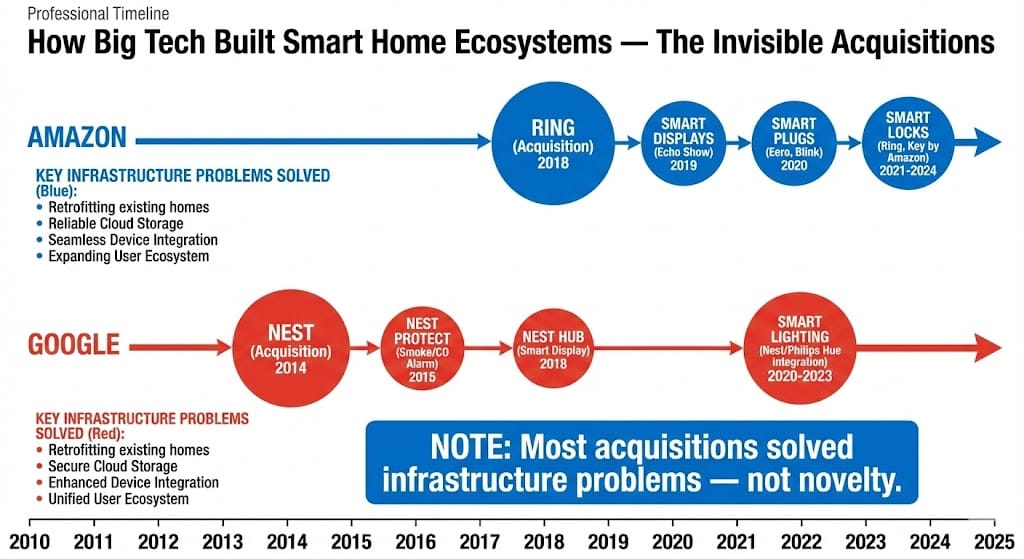

Amazon did this with logistics. Google did this with fiber and infrastructure. Apple did this with semiconductor design and manufacturing. And most visibly, Amazon, Google, and Apple have all done this with smart home infrastructure—acquiring companies that most consumers have never heard of, solving problems most people didn't know existed.

That acquisition pattern is where the real story lives.

Pattern Recognition: Ring, Nest, and the Overlooked Layers

The smart home narrative usually credits Amazon's Ring and Google's Nest as the big breakthroughs. Cameras! Thermostats! Smart home integration!

But both Amazon and Google acquired dozens of smaller companies to actually make those products work as part of a broader system:

Ring (Amazon): To make a doorbell camera useful, you need:

- Cloud infrastructure to store video (acquired or built)

- Notification systems (acquired or built)

- Integration with other Amazon services (Alexa, Prime)

- Last-mile installation logistics

Nest (Google): To make a thermostat autonomous, you need:

- Energy consumption data and algorithms

- Integration with smart building systems

- Compatibility with existing HVAC infrastructure

- Cloud computing for learning algorithms

Neither company could have built these systems by staying focused on the front-end product. They had to acquire or build the invisible infrastructure layers.

Most of those layers were acquired from smaller companies solving unglamorous problems: how to retrofit existing systems, how to integrate with legacy infrastructure, how to handle the messy reality that most homes aren't built for automation.

Ring 一 Acquired by Amazon for $1.2 Billion

Nest - Acquired by Google for $3.2 Billion

Big Tech investments have resulted in significant returns for early investors in these companies - so, which area of the smart home is next?

RYSE is a tech startup poised to dominate the Smart Shades market, with an exclusive public offering of shares priced at just USD $2.35.

They are filling in one of the last missing pieces of the smart home, with:

- Proven Demand: Offering the only product that automates existing window shades, RYSE has sold over $10M of product to date.

- Powerful Patents: RYSE has over 10 granted patents, and an Amazon Court Judgement win that blocks the sale of any copycats from selling.

- Consistent Returns: Early shareholders have seen their share price rise by over 10x, with significant upside remaining as RYSE launched in over 100 BestBuy stores.

Invest in this exclusive public offering before the round closes!

This email contains a paid advertisement for the Ryse Regulation A+ offering. Please review the offering circular at https://invest.helloryse.com/

Infrastructure Beats Novelty

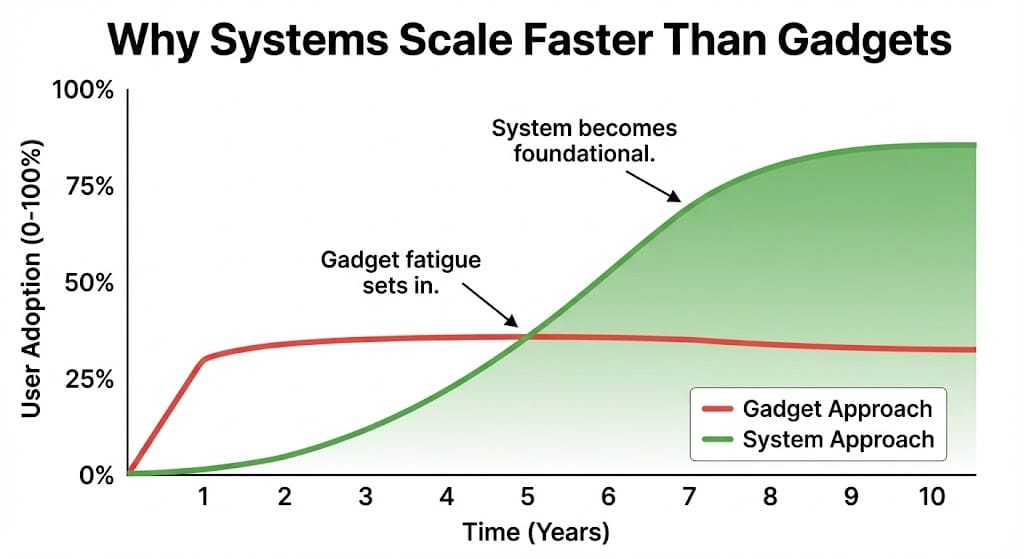

Here's an observation that rarely gets stated: infrastructure technology scales faster and larger than novelty technology.

A novel app might get millions of users quickly, but those users are often playing with it rather than depending on it. Infrastructure technology gets fewer users faster, but those users depend on it completely.

The smart home scaled not because cameras and thermostats were novel (they weren't—both existed in various forms), but because Big Tech solved infrastructure problems that made those products actually useful as part of a larger system.

Before Ring and Nest, you could buy smart cameras and thermostats separately. But they didn't talk to each other. They didn't integrate with how people actually lived. They were novelties—cool toys, not foundational infrastructure.

Once Ring and Nest arrived as part of larger ecosystems (Amazon's and Google's), with integration layers and cloud backends and multiple access points, they became infrastructure. You could imagine building a home automation system on top of them.

The Smart Home as System, Not Gadget Collection

This distinction matters enormously.

A gadget is something you buy because it's cool or interesting. You use it, maybe you like it, maybe you stop using it.

A system is something you build that depends on multiple components working together. Once you've invested in a system, switching costs are high, and you're likely to keep adding to it rather than replacing it.

Amazon and Google understood this: don't compete on individual products. Compete by owning the system layer.

Ring and Nest weren't bought because they were gadgets. They were bought because they represented gateway products into larger home automation systems. Amazon could offer Ring, then leverage that connection to sell smart speakers, smart displays, lighting, locks, security systems—all integrated through a common infrastructure.

The genius wasn't any single product. It was recognizing that home automation would scale only if there was a unified system layer, not a collection of incompatible gadgets.

The Last-Mile Problem: Retrofitting vs. Replacing

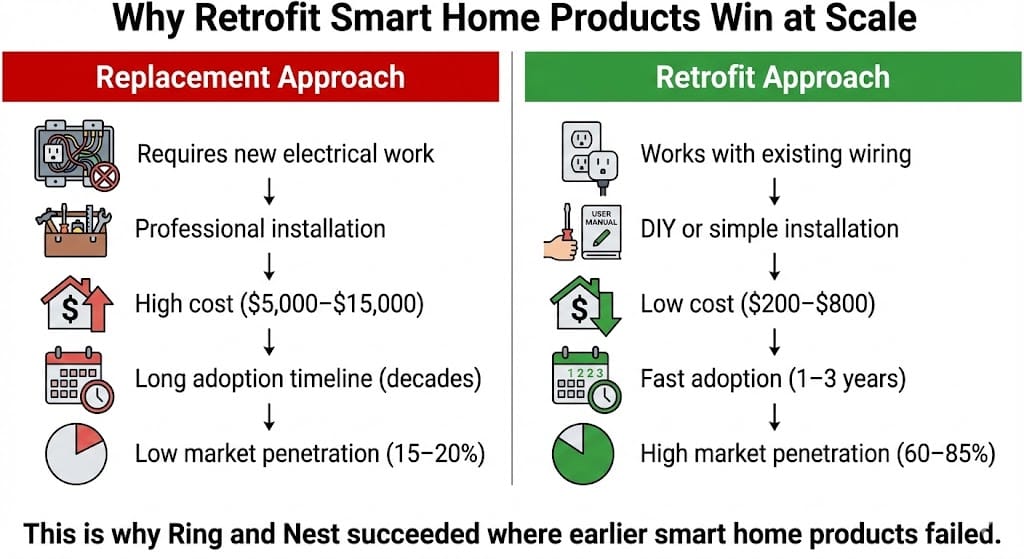

The real infrastructure problem Big Tech had to solve wasn't innovation. It was compatibility with existing homes.

Most smart home products fail because they require replacing or rewiring existing infrastructure. New wiring. New electrical work. Installation that only professionals can do.

But smart home adoption happens when you can add automation to existing homes without tearing walls apart. You need products that:

- Work with existing wiring

- Integrate with existing systems (HVAC, lighting, locks)

- Install without professional help

- Don't require replacing things that already work

This is why Ring and Nest succeeded where earlier smart home products failed. They solved the retrofitting problem.

Ring works with existing doorbell wiring. Nest works with existing thermostat wiring. Neither requires replacing your home's foundational infrastructure—they sit on top of it.

That's infrastructure thinking: not replacing the entire system, but adding a smart layer on top of what already exists.

Mini-Case: Why Automating What Exists Scales Faster

There's a principle in software and hardware: automating what already exists scales faster than replacing it.

If you can add automation to existing HVAC systems, you can reach millions of homes in months. If you require replacing HVAC systems, adoption takes decades and never reaches saturation.

This is why most successful smart home products are retrofits—cameras that work with existing doorbell wiring, thermostats that work with existing HVAC systems, locks that work with existing door hardware.

By contrast, products that required replacing existing infrastructure (entire new smart home platforms, new electrical systems, new communication protocols) failed to scale. The switching cost was too high.

Big Tech acquisition strategy reflected this understanding: acquire companies that solved retrofitting problems, not replacement problems.

Consumer Tech vs. Infrastructure Tech

The distinction matters for understanding where scale actually happens:

| Consumer Tech (Gadgets) | Infrastructure Tech (Systems) |

|---|---|

| Novelty drives adoption | Compatibility drives adoption |

| High switching costs initially | High switching costs eventually |

| Success measured in user excitement | Success measured in system integration |

| Margins high initially, compress over time | Margins modest, persist if system is durable |

| Headlines prominent, then fade | Headlines minimal, compound invisibly |

| Replaced by next novelty regularly | Persist for decades once established |

| "Cool" is the value proposition | Utility and compatibility are value |

Big Tech's acquisition strategy targets infrastructure tech, not gadget tech. They buy boring.

Why Patents and Distribution Matter More Than Virality

The acquisitions Big Tech makes often target companies with:

Patents and IP: Intellectual property around how to integrate with existing systems, how to retrofit, how to make incompatible things work together.

Distribution: Existing relationships with installers, contractors, electricians, builders—the people who actually put things in homes.

User base: Existing customers and install base, which becomes part of the larger ecosystem.

These are worth billions, but they're unsexy and unglamorous. You can't make them trend on social media. You can't write compelling narratives about "how this startup is disrupting smart homes."

But they're how large-scale infrastructure actually gets built.

The Signal: Early Infrastructure Layering

Some early-stage companies focus on automating existing home infrastructure rather than replacing it. Educational materials exist that outline how certain smart-home platforms approach this layer and why incumbents often acquire rather than build.

The signal isn't novelty. It's compatibility and retrofitting focus. Companies that understand how to add automation layers on top of existing infrastructure, rather than requiring replacement, attract acquisition attention from Big Tech.

Why Big Tech Buys When Systems Are Already Working

Here's the insight most people miss: Big Tech acquires when systems are already working, not when they're revolutionary.

They don't acquire because they think the product is brilliant. They acquire because they recognize it solves an infrastructure problem that's already proven to be real.

Ring was acquired because doorbell cameras were already selling. Nest was acquired because smart thermostats were already scaling. The acquisitions recognized working solutions to infrastructure problems, then positioned them within larger ecosystems.

This is the opposite of how venture capital works (invest in unproven ideas and hope they scale). Big Tech's strategy is to acquire proven infrastructure solutions and integrate them into larger systems.

Reflection: Why Boring Is Where Scale Lives

Most of the biggest technological shifts in history didn't feel exciting when they were beginning. Electricity infrastructure. Telecommunications. Water systems. None of these were exciting. They were boring infrastructure improvements.

But boring infrastructure improvements compound. They reach everyone. They become invisible because they're everywhere.

The smart home will reach saturation not through novelty, but through boring, incremental infrastructure improvements that make adding automation to existing homes cheaper and easier.

The companies building the actual smart home infrastructure—the boring ones solving retrofitting problems, integration challenges, and compatibility issues—are invisible to most people.

Their stories don't trend. Their products don't go viral. They don't have charismatic founders giving TED talks.

But they're being acquired by Big Tech for billions because they've solved real infrastructure problems that don't have novelty appeal, but have massive scale potential.

That's where the real value is. Not in what looks exciting today, but in what infrastructure solves boring problems in ways that let everyone else build on top of them.

The most transformative technologies rarely look revolutionary. They just look like invisible layers that eventually support everything else.

—

Claire West