The Map That Changes Everything

The analyst spreads the supply chain diagram across the desk. It’s not a headline. It’s not a press release. It’s a map—boxes and arrows showing how dysprosium moves from a mine in southern China through a separation facility in Ganzhou, into a magnet factory, and finally into a precision guidance system. The analyst stares at one arrow in particular: the box labeled "processing equipment." That box, she realizes, controls everything else. No equipment, no separation. No separation, no magnets. No magnets, no system.

This is how power works in 2025. Not through price spikes. Not through trade wars. Through control of the smallest physical inputs—the ones that modern systems cannot function without.

What Actually Changed

In April 2025, China’s Ministry of Commerce announced export licensing requirements for seven rare earth elements. In October, it expanded the list to twelve of the seventeen rare earths, adding holmium, erbium, thulium, europium, and ytterbium. The announcement received coverage, but the mechanics remained obscure. These were not blanket bans. They were licensing requirements, with applications assessed based on end-user, end-use, and destination.

More significantly, China imposed controls on the export of processing equipment—over 20 categories covering mining, smelting, separation, crystallization, and permanent magnet manufacturing. Foreign manufacturers must now obtain Chinese licenses to export products containing more than 0.1 percent Chinese-origin rare earths, even if manufactured outside China. The rules extend extraterritorially: a magnet made in Vietnam using Chinese-separated dysprosium requires Chinese approval.

The system functions as a valve, not a wall. Beijing can modulate flow, target specific industries, and gather intelligence on downstream users. Defense applications face automatic denial. Advanced semiconductor uses receive case-by-case review. The bureaucracy itself becomes a weapon: licensing delays, documentation requirements, and end-use verification create friction that propagates through entire value chains.

This is not trade policy. It is infrastructure governance.

China just weaponized the metals that power AI, EVs, and defense.

Only one U.S. company can produce them — and Trump could be ready to give it “national security” status.

If that happens, its stock won’t just rise. It’ll detonate.

AI runs on these rare earths. Data centers, Teslas, missiles — all depend on them.

This is the next great American comeback story… and the profits could be legendary.

Before the news cycle catches up — get the full briefing now:

See What Trump’s Next Pick Could be Before D.C. Moves

Why These Metals Matter

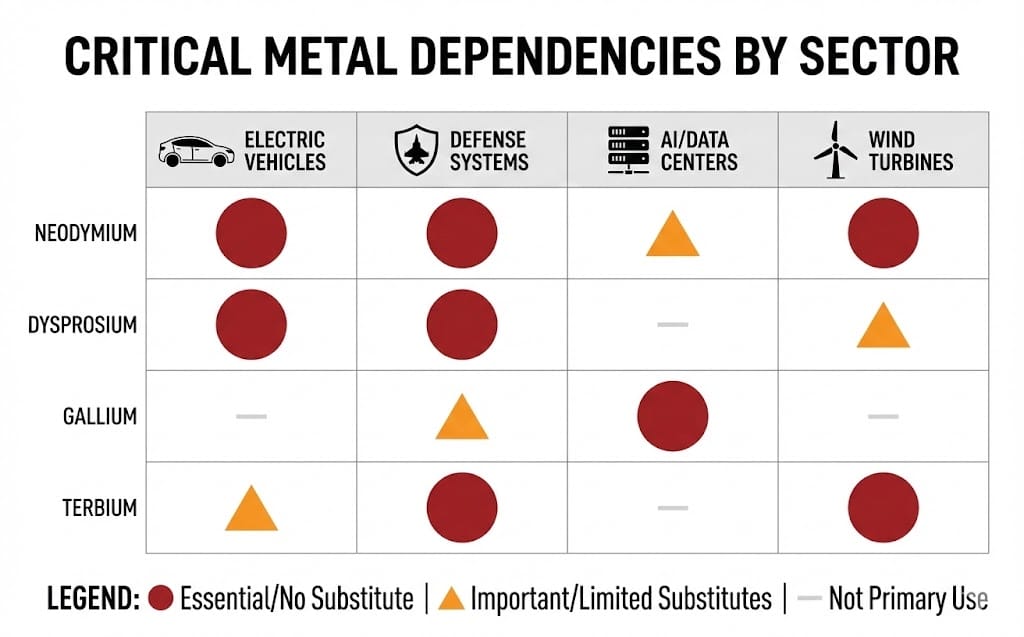

Rare earth elements are not rare geologically, but they are rare economically—because processing them requires specialized infrastructure that cannot be built quickly or cheaply. The heavy rare earths—dysprosium, terbium, ytterbium—are essential for high-performance permanent magnets. These magnets operate at temperatures above 150°C, making them indispensable for electric vehicle motors, wind turbine generators, and precision-guided munitions.

Neodymium-iron-boron magnets, enhanced with dysprosium and terbium, power the motors in EVs. A single motor requires 1-2 kilograms of rare earth magnets. Without them, power density drops, efficiency falls, and vehicles become heavier and less competitive.

In defense, these magnets enable miniaturization. They sit in the actuators of F-35 flight control surfaces, in the guidance systems of Tomahawk cruise missiles, in the gimbals of targeting pods, and in the electric drives of next-generation naval vessels. Samarium-cobalt magnets, resistant to demagnetization at high temperatures, operate in jet engines and hypersonic vehicle components.

AI infrastructure depends on rare earths at multiple points. Gallium and germanium, now under Chinese export controls, are critical for advanced semiconductors. Rare earth phosphors enable high-resolution displays for command centers. The magnets in server cooling fans and hard drive actuators require neodymium. The entire stack—chips, power systems, thermal management—rests on a foundation of controlled materials.

Grid stability, increasingly reliant on battery storage and renewable generation, faces the same dependency. Wind turbines use up to 600 kilograms of rare earth magnets per megawatt of capacity. Battery management systems require gallium-based semiconductors for efficient power conversion.

These are not optional inputs. They are structural components of modern systems.

The Illusion of Diversification

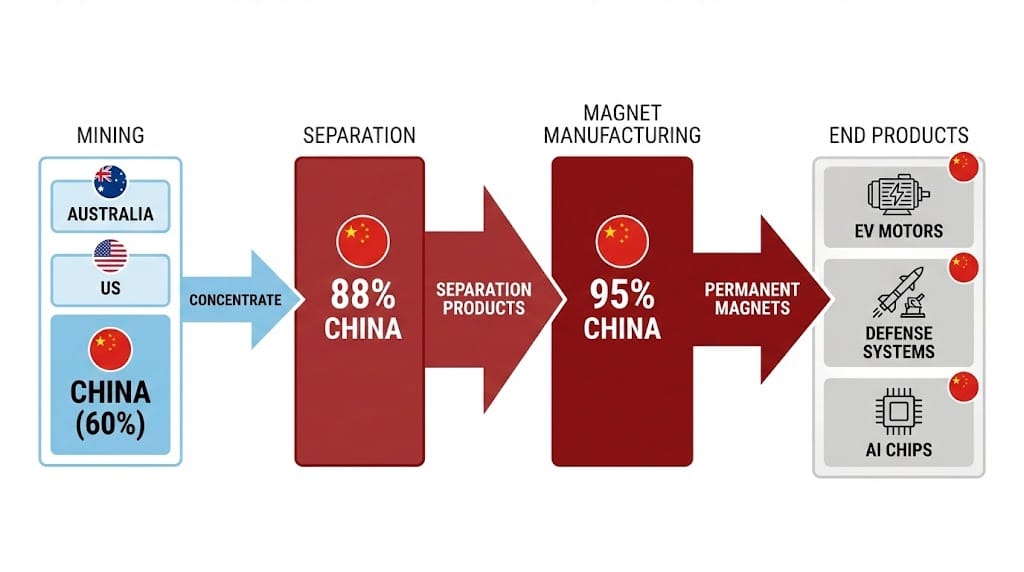

The conventional response to supply risk is diversification: develop mines in Australia, the United States, Canada, and Africa. This assumes that mining is the choke point. It is not.

China controls 60% of global rare earth mining, but 88% of smelting and separation, and 95% of permanent magnet manufacturing. A new mine outside China produces concentrate. That concentrate must be shipped to China for separation because no other country has built the specialized solvent extraction capacity at scale. The processing facilities require not just capital—$500 million to $1 billion per plant—but proprietary knowledge accumulated through decades of operational experience.

The "global supply chain" is a misnomer. It is a Chinese supply chain with foreign feedstock. Until alternative processing infrastructure exists, mining diversification creates only the illusion of resilience.

This becomes clear when examining the 2025 controls. China restricted exports of seven rare earths in April. Magnet exports dropped 75% in the following two months, forcing production pauses at some automakers. The bottleneck was not raw material availability. It was the licensing system and the concentration of processing capacity.

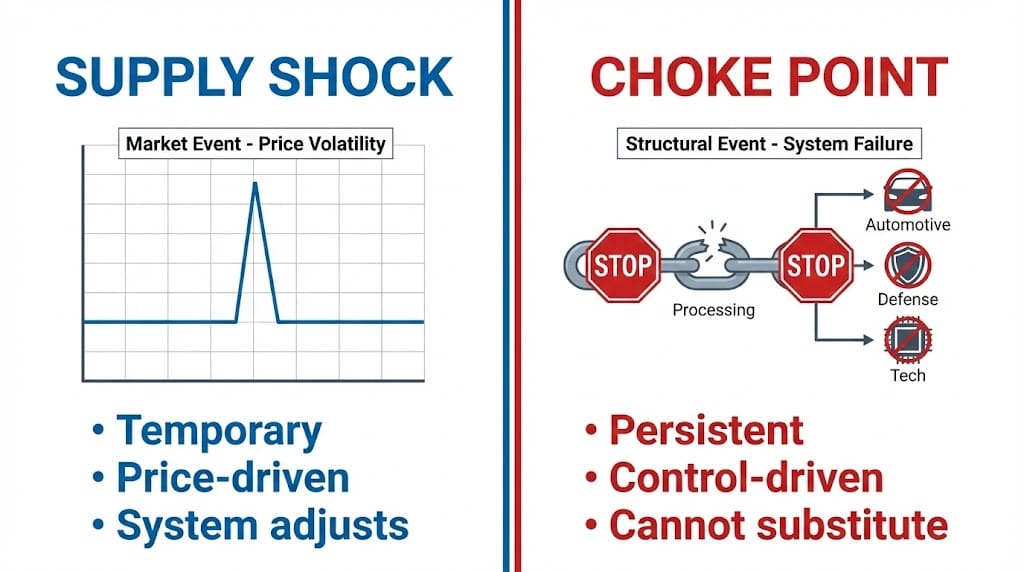

Choke Points vs. Markets

A supply shock is a market event. A mine floods, prices spike, buyers scramble, and the system adjusts. New supply comes online, prices normalize. The architecture remains intact.

A choke point is a structural event. It occurs when a single entity controls a input that cannot be substituted or quickly replicated. The system does not adjust—it fragments. Buyers must choose between compliance and operational paralysis.

China’s 2010 embargo on rare earth exports to Japan demonstrated this distinction. After a maritime dispute, Beijing halted shipments. Prices soared, but more importantly, Japanese manufacturers could not source materials regardless of price. The choke point was absolute. Japan responded by creating the Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC), which finances overseas mining projects and stockpiles strategic materials. It also accelerated R&D into recycling and substitution—a tacit acknowledgment that market solutions were insufficient.

The 2025 measures are more sophisticated than 2010. They target not just raw materials but the equipment and knowledge required to build alternative capacity. By controlling technology exports, China raises the cost and timeline for competitors attempting to replicate its processing infrastructure. This is not about short-term price leverage. It is about maintaining structural dominance as demand grows.

How Governments Respond: A Mini-Case

When strategic materials become weaponized, governments shift from market participants to system architects. The pattern is consistent.

In 1939, as Nazi Germany threatened access to tungsten and chromium, the United States created the Strategic and Critical Materials Stock Piling Act. The government did not rely on market signals. It built physical reserves, financed domestic production, and used defense contracts to guarantee demand.

In 1973, after the oil embargo, Washington created the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. The reserve was not a commercial inventory. It was a systemic buffer designed to break a choke point.

In 2025, the U.S. Department of Defense took an equity stake in MP Materials and guaranteed floor prices for rare earth production, anchoring a mine-to-magnet pathway in California. This is not industrial policy in the traditional sense. It is strategic material governance—the recognition that national security requires control over physical inputs, not just financial exposure.

Japan’s approach combines stockpiling, long-term offtake agreements, and aggressive R&D into recycling and substitution. The European Union’s Critical Raw Materials Act aims to build processing capacity within Europe, but faces the same knowledge and equipment constraints that China now controls.

The common thread: governments move from supporting markets to building parallel systems. Capital flows follow security designation, not earnings forecasts.

Why National Security Status Matters

When the U.S. Department of Defense designates a material as strategic, three mechanisms activate:

- Capital flows: The Defense Production Act allocates billions to domestic production. Private capital follows, seeking derisked returns.

- Stockpiling: The National Defense Stockpile begins acquiring material, creating a price floor and guaranteed demand.

- R&D prioritization: Federal labs and university programs receive funding for substitution and recycling research, accelerating technological alternatives.

These are not political gestures. They are mechanical shifts in resource allocation that reprice assets before markets adjust. A rare earth deposit in California is worth more after Pentagon designation because its cash flows are effectively guaranteed.

China understands this. Its export controls are calibrated to avoid triggering a full-scale Western response while demonstrating the capacity to weaponize supply chains. The one-year pause announced in November 2025—suspending some restrictions until November 2026—was framed as a diplomatic gesture following the Trump-Xi meeting, but it preserves the underlying control architecture. Beijing retains the valve. The West receives temporary relief while structural dependencies remain unchanged.

The Quiet Turn: Capital Moves Before Designation

Institutional investors tracking critical minerals have shifted from price forecasts to capability mapping. They analyze not just reserves, but separation capacity, equipment supply chains, and licensing regimes. They understand that control over processing equipment is more valuable than control over mines.

Some analysts are tracking one U.S.-based producer positioned at the center of this supply shift. A briefing outlines how national security designation could change its role—and why attention is moving now, before policy announcements. The logic is straightforward: once designation occurs, government contracts and stockpiling programs will reprice the asset, but the window for strategic entry will have closed.

This is not speculation. It is systems analysis. The choke points are visible in MOFCOM notifications, equipment export bans, and licensing requirements. The capital that moves early is not betting on politics. It is positioning for mechanical inevitability: either the West builds alternative capacity—a ten-year project—or it accepts managed dependence. Both paths create winners, but only those positioned before the policy shift benefit from the repricing.

The Next Decade

The narrative of technological progress—AI, electrification, autonomous systems—assumes material abundance. That assumption is now being tested. The constraint is not software architecture or algorithmic efficiency. It is the physical availability of elements that enable systems to function at scale.

China’s export controls are not a trade war tactic. They are a structural feature of a world where economic power derives from control over physical inputs. The 2025 measures demonstrate that processing capacity, not raw material reserves, is the decisive node. By restricting equipment exports, China ensures that building alternative capacity remains slow, expensive, and uncertain.

The next decade will not be defined by the speed of innovation alone. It will be defined by access to the materials that make innovation deployable. This is not a speculative claim. It is visible in supply chain diagrams, MOFCOM notifications, and the strategic material plans of every major power.

The map on the analyst’s desk is not a forecast. It is a snapshot of a system under strain. The arrows point in one direction: toward concentration. The question is not whether the West will respond, but whether it can respond fast enough to matter. The math is mechanical. The time windows are narrow. And the quiet turn is already underway.

—

Claire West