The Quiet Heaviness of Everyday Prices

It is a Tuesday morning in late 2025. You are buying groceries. The same items you bought last month—milk, bread, coffee, detergent. The total is $127. Last month it was $119. The month before, $112. Nothing dramatic. No crisis. Just a consistent, quiet heaviness—each trip slightly more expensive than the last, each dollar buying slightly less.

This is not the inflation of headlines. Headline inflation in September 2025 was reported at 3.0 percent annually. But your grocery bill increased 7 percent. Your insurance premium rose 9 percent. Your rent renewal came with an 8 percent increase. The gap between what is reported and what is lived is not error. It is structure.

Inflation is not a statistic. It is an experience. And when the experience diverges from the headline, capital adjusts quietly, not loudly.

The Difference Between Reported and Lived Inflation

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) measures a weighted average of prices across thousands of goods and services. It is designed to represent the average household's consumption basket. But no household is average.

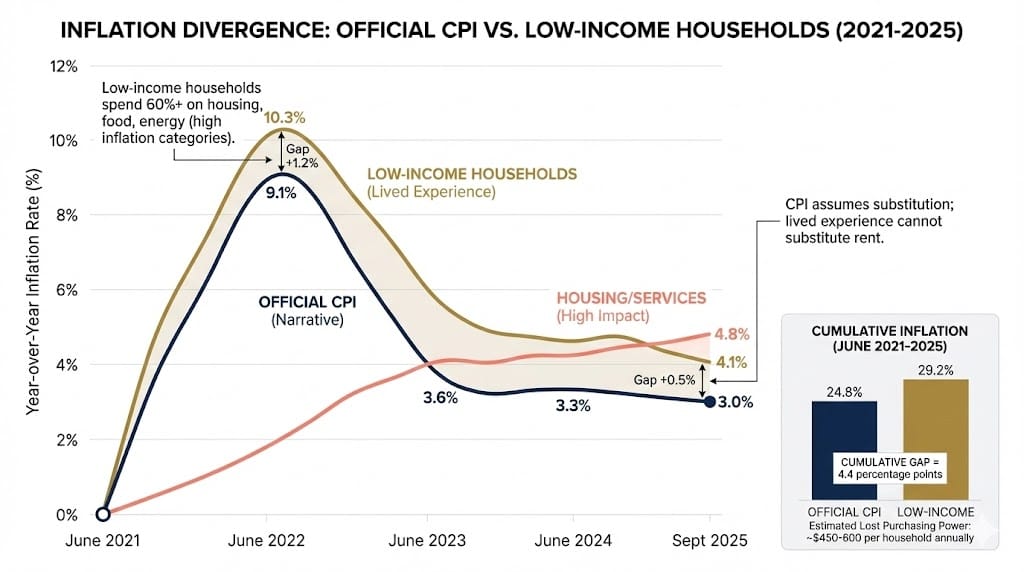

Low-income households spend disproportionately on housing, food, and energy. In June 2025, while headline CPI measured inflation at 3.6 percent, low-income households experienced inflation at 4.1 percent—a 0.5 percentage point gap that compounds month after month. For housing and household services specifically, inflation ran at 4.8 percent, not 3.6 percent. For food, the gap is similar.

This divergence is not temporary. Between June 2021 and June 2025, low-income households experienced cumulative inflation of 29.2 percent, while CPI measured 24.8 percent. That 4.4 percentage point difference represents hundreds of dollars in lost purchasing power for families least able to absorb it.

The reason is methodological. CPI uses a fixed basket that assumes consumers substitute cheaper alternatives when prices rise. But substitution has limits. You cannot substitute rent. You cannot substitute insulin. You cannot substitute gasoline for your commute. The lived experience of inflation is therefore stickier, more persistent, and more painful than the reported average.

The government tells you inflation is under control.

But the Chapwood Index—which tracks the real things you actually buy—shows that real inflation has averaged over 11% per year since 2000.

Your money is dying.

That is why the "Smart Money" is exiting the U.S. Dollar.

Tether—the issuer of the world's largest stablecoin—sees the writing on the wall. That is why they are diversifying their $180 billion reserve into physical gold.

They know that the new "GENIUS Act" passed by Washington is just a desperate attempt to force people to buy U.S. debt.

They aren't falling for it. And neither should you.

You need to own gold. But more importantly, you need to own the companies that produce the gold.

These companies are the only asset class that is actually undervalued in a world where everything else is in a bubble.

Click here to see the 4 miners I trust to protect my wealth.

Why Capital Responds to Erosion, Not Announcements

Institutional capital does not wait for policy announcements. It watches purchasing power decay in real time.

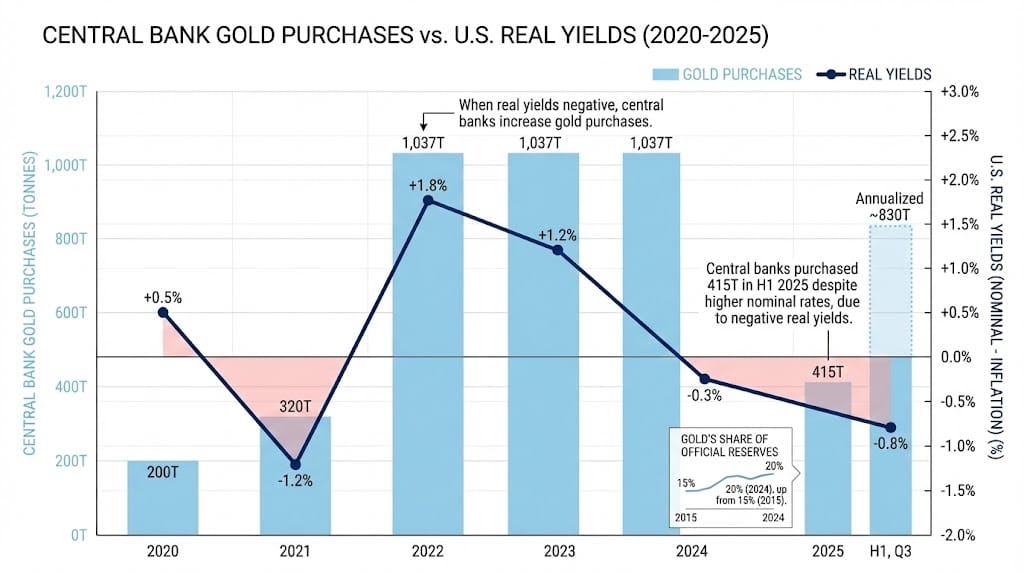

When central banks see inflation running above target while interest rates remain low, they recognize that real yields—nominal rates minus inflation—are negative. Holding cash or government bonds guarantees purchasing power erosion. This is why central banks, beginning in 2022, more than doubled their gold purchases, exceeding 1,000 tonnes annually for three consecutive years.

In the first half of 2025 alone, central banks purchased 415 tonnes of gold. A survey of reserve managers found 71 percent planned to increase gold allocations, while only 2 percent planned to reduce them. Gold's share of official reserves hit 20 percent in 2024, edging out the euro at 16 percent.

This is not speculation. It is balance-sheet management. Central banks are not betting on gold prices. They are protecting against the erosion of their primary reserve assets—currencies that lose purchasing power when inflation persists.

The logic is straightforward: gold pays no interest, but it also cannot be devalued by monetary policy. When real yields are negative, the opportunity cost of holding gold disappears. The risk of holding currency becomes greater than the risk of holding a non-yielding asset.

Gold as a Balance-Sheet Tool, Not a Bet

Gold's role in portfolios is often misunderstood. It is not a growth asset. It is not a speculation on crisis. It is a balance-sheet tool—a way to hold wealth outside the monetary system when that system's stability is uncertain.

Historically, gold has served this function during monetary transitions. In the 1970s, as inflation eroded the dollar's value, gold rose from $35 to over $800 per ounce—not because gold became more valuable, but because the dollar became less valuable. The purchasing power of gold remained relatively stable; the purchasing power of currency collapsed.

Today, similar dynamics are visible. Central banks are not buying gold because they expect a crisis. They are buying gold because they see persistent fiscal deficits—6 percent of GDP in the United States with no consolidation plan—and they recognize that the policy path forward involves either higher inflation or explicit currency devaluation.

Gold functions as a monetary constant. It cannot be printed. It cannot be defaulted on. It has no counterparty risk. When trust in paper stability weakens, gold quietly re-enters balance sheets—not as a trade, but as a tool.

Case Context: Reserves Diversification

Large reserve holders—sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, endowments—face the same calculus as central banks, but with fewer constraints. They can diversify into productive assets, real estate, infrastructure. Yet many are choosing to allocate to gold producers, not just gold metal.

The reason is subtle but important. Owning a gold bar is owning a commodity. Owning a gold mining company is owning productive capacity—the ability to extract more gold, generate cash flow, and compound value over time.

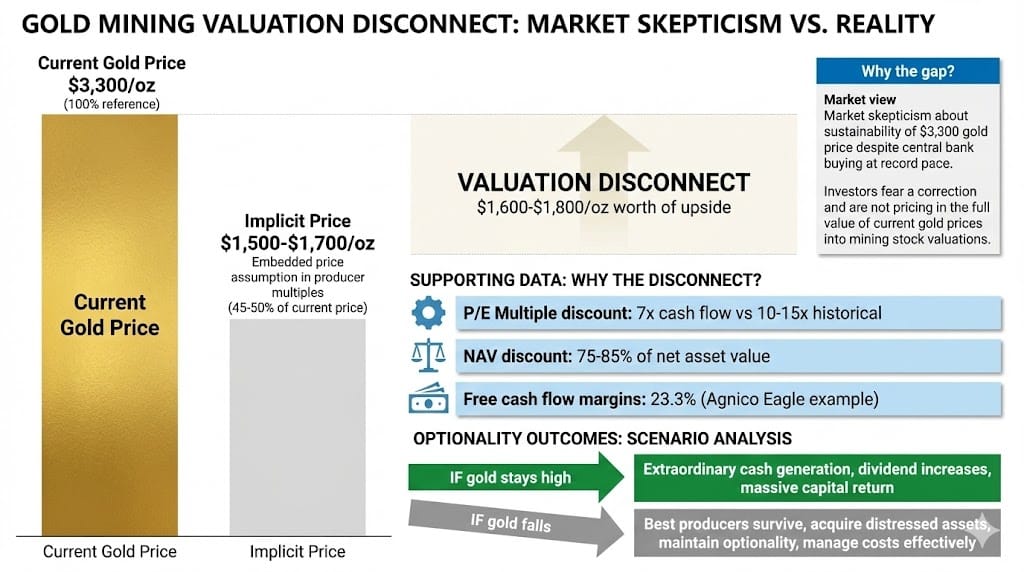

In 2025, gold mining companies trade at approximately 7x cash flow, compared to historical norms of 10-15x. They sell at 75-85 percent discounts to net asset value. Major producers like Agnico Eagle generate free cash flow margins of 23.3 percent with debt-to-equity ratios below 25 percent. These are not speculative ventures. They are cash-generating businesses trading at compressed valuations.

When currency erosion is the primary risk, owning productive capacity that generates real assets becomes more attractive than owning the assets themselves. The company can grow. The metal cannot.

Narrative Inflation vs. Operational Inflation

| Dimension | Narrative Inflation | Operational Inflation |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement | CPI, PCE, core inflation (ex-food/energy) | Household-specific cost baskets, housing, insurance, food |

| 2025 Level | 3.0% (CPI, September) cnbc | 4.1% (low-income households) rss; 4.8% (housing/services) ons |

| Composition | Weighted average across all goods/services | Concentrated in non-substitutable essentials (rent, healthcare, utilities) |

| Policy Response | Interest rate adjustments, quantitative tightening | None; these categories are immune to monetary policy |

| Capital Impact | Affects bond yields, currency values | Affects real purchasing power, living standards |

| Time Horizon | Short-term (monthly/quarterly) | Long-term (cumulative erosion over years) |

| Visibility | High (headlines, Fed statements) | Low (individual experience, not aggregated) |

| Who Tracks It | Markets, media, policymakers | Households, institutional capital (quietly) |

| Asset Response | Bonds sell off, rates rise | Gold accumulation, real assets, producer equities |

The gap between columns is where wealth is quietly lost or preserved. Narrative inflation drives policy. Operational inflation drives behavior.

Why Producers Matter More Than Price Charts

There is a difference between owning a commodity and owning the capacity to produce it. This distinction becomes critical during periods of currency erosion.

A gold bar holds value but generates no income. A gold mining company holds reserves, generates cash flow, and can expand production. When gold prices rise, producer margins expand exponentially because costs are relatively fixed. When gold prices fall, disciplined producers with low debt and long-life assets survive while marginal players exit, consolidating market share for the survivors.

In 2025, gold miners trade at valuations that imply gold prices of $1,500-$1,700 per ounce, despite market prices above $3,300. This valuation gap suggests the market is pricing in a significant decline or disbelieving the sustainability of current prices. Yet central bank buying continues at record pace, and fiscal deficits show no sign of contraction.

The disconnect between producer valuations and metal prices creates an asymmetry. If gold prices remain elevated, producers generate extraordinary cash flows. If gold prices fall, the best producers survive and acquire distressed assets. In either scenario, owning productive capacity offers optionality that owning the metal does not.

Prudence, Not Urgency

Understanding erosion is not fear. It is literacy.

When purchasing power declines 4 percent annually, a portfolio must earn 4 percent just to stay even. When government bonds yield 3 percent, they guarantee a loss. When cash yields 4 percent but inflation is 5 percent, the real value of savings declines.

These are not dramatic statements. They are arithmetic. Ignoring them is riskier than acknowledging them.

Preparation does not require panic. It requires quiet maintenance—rebalancing portfolios to include assets that preserve purchasing power, not because of crisis, but because of erosion. Gold and gold producers are not bets on collapse. They are tools for maintaining capital in an environment where paper assets are systematically devalued.

Wealth Preservation as Quiet Maintenance

The most effective financial decisions in 2025 are not dramatic. They are boring. They involve recognizing that headline inflation understates lived inflation, that central banks are quietly accumulating gold, that producers are undervalued relative to metal prices, and that fiscal deficits make currency erosion a structural feature, not a cyclical bug.

This is not a call to action. It is a call to awareness. Capital adjusts quietly because it must. Individuals who understand why it adjusts can make the same quiet adjustments—rebalancing, diversifying, maintaining—without drama, without urgency, and without fear.

Wealth preservation is not a trade. It is maintenance. And maintenance works best when it is steady, deliberate, and based on what is actually happening, not on what is officially reported.

—

Claire West