The Tool Is Not the Prediction

There is a moment in nearly every investor's career when the choice becomes clear: they can be right about an asset, or they can be right about the decision-making process. These are not the same thing.

Most investors have been right about assets. They bought gold when it was cheap. They identified good companies before the market recognized them. They understood sector rotations. And yet their portfolios underperformed the benchmarks those assets were supposed to beat. This paradox—being right about what to buy but wrong about when to sell it, or when to hold it, or when to stop panicking about it—is the central nervous system of portfolio failure.

The culprit is not the assets themselves. It is the decision-making process that surrounds them.

Why Good Portfolios Still Underperform

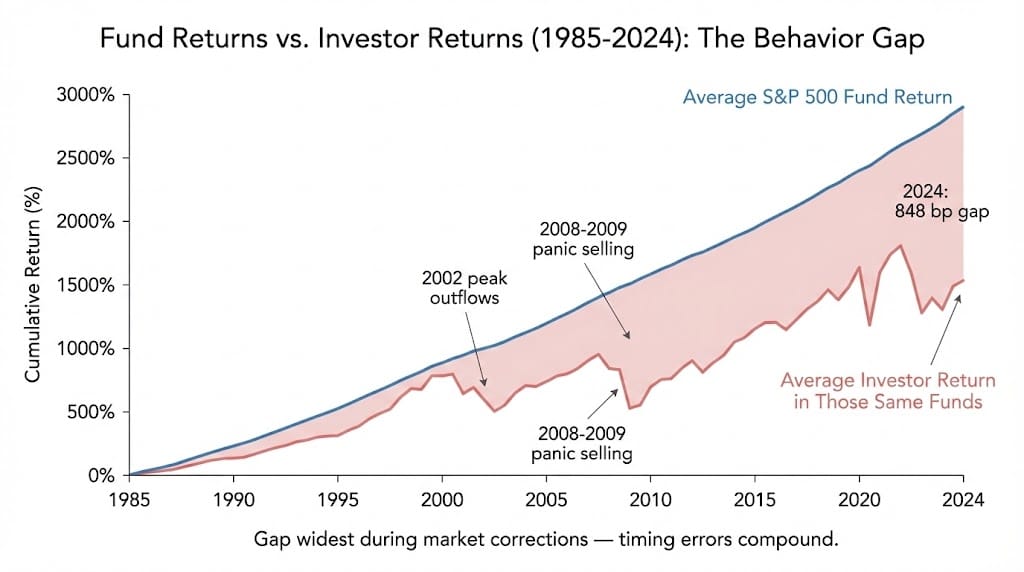

The data is now irrefutable after four decades of continuous measurement. The DALBAR Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior tracks mutual fund investor behavior from 1985 to 2024. In 2024, the average equity investor earned 16.54 percent. The S&P 500 returned 25.05 percent. The gap was 848 basis points—the second-largest performance gap in the past decade.

This was not because investors chose the wrong funds. Most of these investors owned diversified, reasonably managed mutual funds with legitimate track records. The underperformance came from behavior: outflows in every quarter of 2024 occurred before major return surges. Investors sold at lows, not highs, simply because they could not tolerate the volatility.

Morningstar's 2024 Mind the Gap study found that over a ten-year period, the average allocation investor earned 6.3 percent annually while their funds produced 7.3 percent—a gap of roughly one percent per year, compounded across a decade. The study noted that volatility had a larger impact on returns than fees. In other words, the damage was not expensive—it was emotional.

A 2024 analysis by a George Mason University finance professor examined the return gap (the difference between what a fund returned and what the average investor in that fund actually earned) across all dollar-denominated mutual funds from 2015 to 2024. The finding: before COVID (2015-2019), poor timing cost investors 0.53 percent per year. After COVID and through 2024, that cost had widened measurably, suggesting the problem is accelerating.

The investor is not being sabotaged by markets. The investor is being sabotaged by himself.

What's the #1 investment today?

It's not a stock. Not crypto. Not gold.

It's a tiny device weighing less than 3 ounces.

Why? Because its software doesn't tell you what to buy. But it could help you transform how your existing portfolio performs.

We back tested it on the worst stocks in history. They would've turned from losers into winners.Even Buffett's legendary results could have improved.

Click here now to watch the full presentation.

The Limits of Forecasts and "Hot Picks"

This is where the conventional advice breaks down. The industry teaches investors to "do their research," to "find good stocks," to "time entry points carefully." But research has also shown that expertise at prediction does not translate into execution discipline.

Consider fund managers—professionals with teams, data, and incentive structures designed to outperform. A 2023 study examining 15,434 shareholder reports from 1,969 funds between 2006 and 2018 found that fund managers display what researchers call self-attribution bias: they take credit for good outcomes and blame external factors for bad ones.

The finding: managers who were 40 percent more likely to internalize success and externalize failure then traded more frequently in the subsequent period. And managers who traded more frequently underperformed. They were more confident, more active, and worse at investing. The forecast skill existed; the discipline did not.

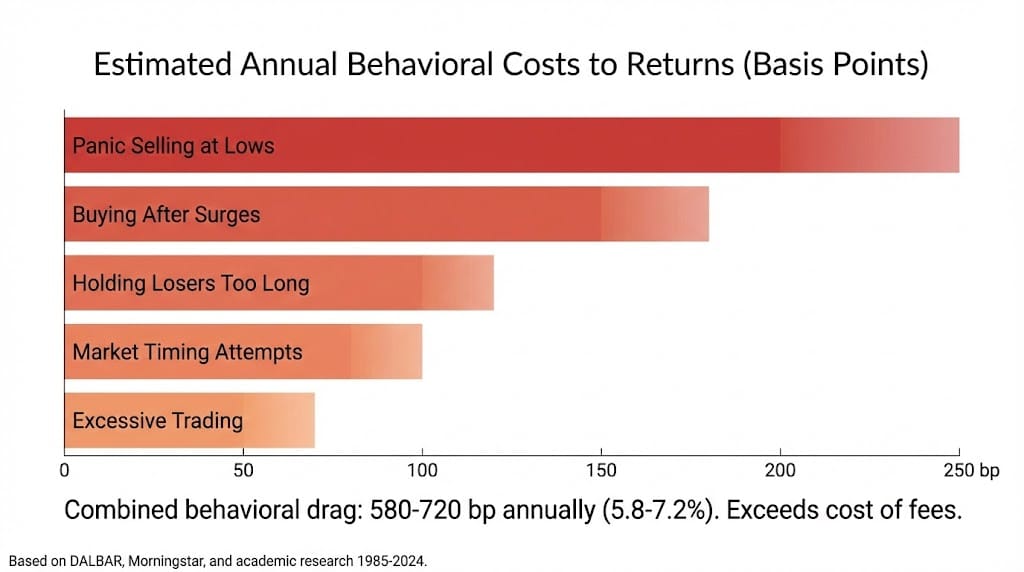

The hot pick, the tactical call, the contrarian conviction—these can all be correct. But conviction alone does not prevent an investor from selling at the worst possible time, buying back in at the worst possible time, or sitting in cash when the market accelerates upward. The research by DALBAR and others shows that timing decisions—not asset selection—are the dominant drag on returns.

A forecast tells you what might happen. It does not tell you how to behave when it does not happen on schedule.

Behavioral Finance: Why Humans Sabotage Sound Strategy

The psychology is textbook. When markets fall, investors experience loss aversion—the emotional pain of losing money weighs roughly twice as heavily as the pleasure of gaining it. This asymmetry causes panic selling. A portfolio that looked sound at $1 million begins to feel dangerous at $900,000, even if the underlying strategy is intact.

Herding behavior follows. After markets correct sharply, investors see others pulling out and follow suit. DALBAR data shows peak inflows to bond funds occurred after major stock market corrections in 2002 and 2008-2009. But by that time, the opportunity had already passed. Investors were buying stability after the stable moment had come and gone.

Recency bias compounds the problem. Investors overweight recent events. If the market dropped last quarter, it feels more likely to drop this quarter. If the market surged, the current surge feels more inevitable. Studies show this combination of recency bias and fear of missing out (FOMO) reduces returns by 1.5 to 2.5 percent annually across investor populations.

None of this is rational. All of it is predictable. And the fact that it is predictable means it can be engineered out of the system.

Institutional Reality: Systems Over Opinions

The greatest wealth managers do not succeed because they have better forecasts. They succeed because they have better systems.

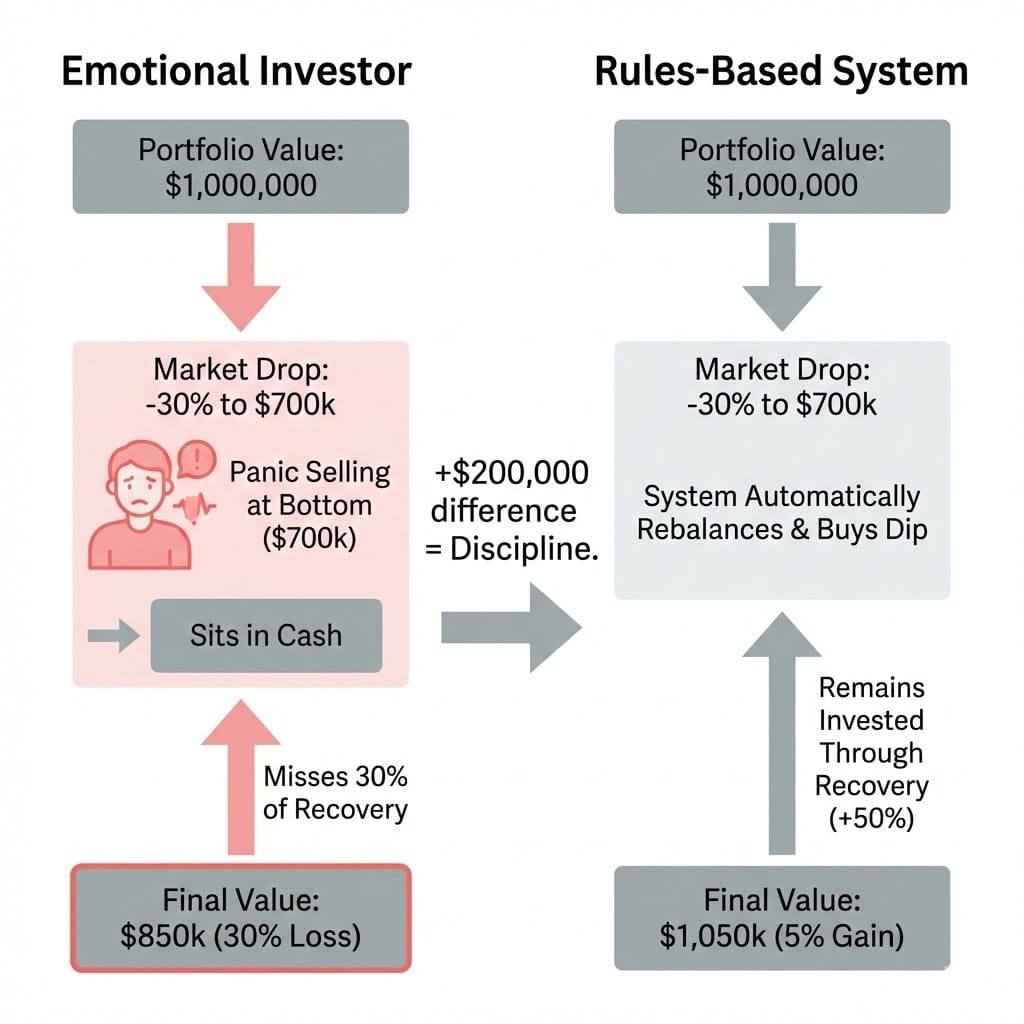

An institutional investor with a 10-billion-dollar portfolio faces the same behavioral hazards as a retail investor with $100,000. The difference is that institutional money is not managed by conviction. It is managed by process. A pension fund does not decide each quarter whether it "feels like" staying in equities. It rebalances according to a predetermined rule. When equities exceed their target weight, the system sells. When they fall below, the system buys.

This is mechanical. It is unemotional. And it is precisely why institutions outperform—not through insight, but through discipline.

Some of the most sophisticated recent research examines AI-assisted portfolio management, specifically hybrid systems where algorithms handle execution and humans provide oversight. The findings are striking: investors using AI-assisted rebalancing tools displayed lower anxiety, faster decision-making, and fewer emotional trading errors. The system did not make people smarter. It prevented them from becoming stupid.

The critical insight: the tool does not predict outcomes. It manages behavior during execution. It takes the emotion out of timing. It removes the choice to panic.

Asset Selection vs. Decision Infrastructure

| Dimension | Asset Selection | Decision Infrastructure |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | "What should I buy?" | "How should I execute?" |

| Skill Required | Research, analysis, conviction | Discipline, consistency, patience |

| Time Horizon | Can be right tomorrow or in 5 years | Matters across all timeframes |

| Emotional Risk | Moderate (conviction sustains through volatility) | Severe (execution breaks under stress) |

| Measurement | Did you pick the winner? | Did you stay in the winner? |

| Replicability | Difficult (requires insight) | Easy (requires rules) |

| Historical Success Rate | 10-15% of active managers beat benchmarks after fees | Automated systems beat 85%+ of active investors |

| Primary Drag on Returns | Asset allocation (20-30% of underperformance) | Timing and behavior (70-80% of underperformance) |

| Buffered Against Bias? | No—confidence can destroy performance | Yes—rules override emotion |

The gap between columns is where capital is lost or preserved. Sophisticated asset selection is valuable. But it is amplified or destroyed by the quality of the infrastructure that surrounds it.

Why Some Investors Are Moving Toward Decision Engines

A quiet shift is occurring among advisors and institutional allocators: the move away from prediction tools and toward decision-support systems. Not because prediction is impossible, but because execution is fragile.

A rules-based investment system does not promise to outsmart the market. It promises to remove the investor from the decision-making process at critical moments. It says: "When X condition occurs, you will do Y action, regardless of how you feel about current headlines." This is automation not as a shortcut, but as a safeguard.

Automated portfolio rebalancing, for example, triggers when asset allocations drift beyond preset tolerance bands—typically 3 to 5 percent from target weights. The human does not decide whether today is a good day to rebalance. The system decides. The system then executes. And the human is spared the emotional calculus that typically leads to postponement and performance drag.

The cost benefit is substantial: automated rebalancing can reduce costs by 60 to 70 percent relative to manual processes while simultaneously improving discipline and reducing behavioral errors. But the real value is not the cost savings. It is the behavioral insurance.

Studies on AI-assisted rebalancing show that trust in the system depends on three factors: algorithm transparency (you can see the rule), human oversight (a human reviews critical decisions), and error correction (the system can be overridden if something is clearly wrong). When these elements exist, investors not only improve returns—they report lower stress and fewer regrets.

Structure Outperforms Conviction

The final implication is both humbling and empowering. You do not need to be right about stocks to build wealth. You need to be right about how you execute your investment plan when you are wrong about stocks.

Most investors will be wrong about direction, timing, or selection—often all three. The ones who succeed are not the ones with perfect foresight. They are the ones with systems that prevent catastrophic errors during emotional moments.

A well-designed tool that enforces discipline—rebalancing automatically, limiting trading frequency, removing timing discretion—will outperform a brilliant forecast executed with human judgment at critical moments. This is not a theoretical claim. Four decades of DALBAR data confirms it. AI-assisted rebalancing studies confirm it. Institutional outperformance confirms it.

Structure is not glamorous. It does not make for compelling narratives. But structure is what separates investors who are right about their assets from investors who actually capture returns from them. Tools that change behavior matter more than tools that improve prediction. And discipline, deployed systematically, is the only reliable edge that survives market cycles and investor psychology.

Wisdom is not a better forecast. It is a system that prevents you from undoing the things you know to be true.

—

Claire West