When Markets Contradict Themselves: How Structure Survives Volatility

Markets get louder when they're confused.

You notice it during certain periods—when inflation is falling but employment is strong, when the Fed is hiking but earnings are weakening, when asset prices are hitting all-time highs while sentiment surveys show fear. These are moments when the signals contradict each other, and the market, unable to settle on a coherent narrative, becomes noisier.

The noise isn't just price action. It's commentary, contradictions, experts disagreeing publicly, policy makers sending mixed signals. There's an ambient anxiety underneath the market activity—a sense that nobody quite knows what's happening, and that uncertainty itself might be the most dangerous thing.

This is when emotional mistakes compound. Not because markets are crashing, but because the normal anchors—the things people usually rely on to make sense of markets—are unreliable.

The Fed's Bind

The Federal Reserve, like any central bank, faces a fundamental tension:

price stability vs. employment stability.

Theoretically, these objectives are compatible. In practice, they often pull in different directions.

Right now, the contradiction is vivid:

Inflation is cooling (suggesting rate cuts are appropriate).

But employment remains strong (suggesting rates should stay elevated).

The Fed wants to maintain employment without reigniting inflation.

But the tools available—interest rates—affect both simultaneously.

So the Fed finds itself stuck: if they cut too aggressively, inflation rebounds. If they hold rates too high, employment weakens and recession risk rises. There's no perfect answer, which means every decision is a trade-off—and every trade-off is debatable.

This is where contradictions live. The Fed has legitimate reasons for conflicting signals. Markets have legitimate reasons for confusion. And ordinary investors, watching this tension play out, feel genuine uncertainty about what happens next.

That uncertainty is the real stress. Not the market moves themselves, but the inability to confidently predict what policy will do.

President Trump's tariffs are only the tip of the iceberg. A growing threat is poised to widen the gap between the Haves and the Have Nots... Permanently change our economy… And dramatically affect your money, the value of your home, your investments, and your ability to retire.

Volatility Isn't Danger by Default

Here's a distinction worth making: volatility and danger are not the same thing.

Volatility is price movement. It's movement divorced from direction—the stock could go up or down significantly. That's uncomfortable, but it's not inherently dangerous.

Uncertainty is danger. When you don't know why something is moving, when the normal patterns have broken down, when even experts disagree on what comes next—that's when mistakes happen.

During periods of monetary contradiction, volatility is high AND uncertainty is high. The combination is psychologically brutal. You're watching prices swing while simultaneously feeling like the anchors that normally guide decision-making have come loose.

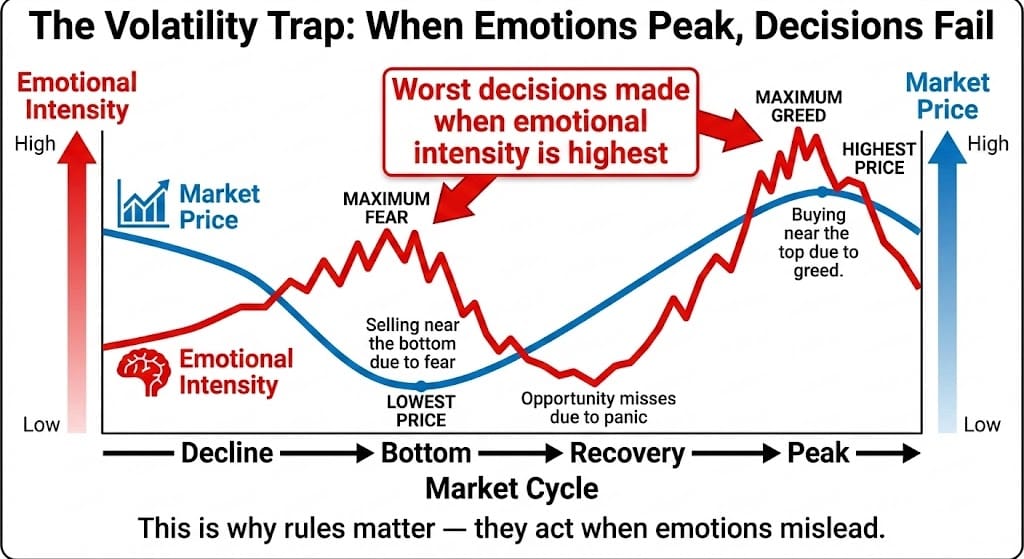

This is when people make their worst decisions:

- Panic selling after a drop (without assessing whether fundamentals have changed)

- Panic buying after a rise (chasing momentum that might reverse)

- Over-trading because they feel like they need to "do something"

- Abandoning long-term plans because short-term noise feels urgent

How Humans Mis-Handle Swings

Behavioral finance has documented the ways humans systematically mis-handle volatility:

Loss aversion: A 10% loss hurts psychologically more than a 10% gain feels good. So during swings downward, people feel urgent pressure to act, even when waiting would be wiser.

Recency bias: The most recent price action feels more predictive than it actually is. A week of selling makes people feel like selling is inevitable. A week of buying feels like inevitability in the other direction.

Anchoring: People fixate on previous highs or lows, treating them as meaningful reference points. "If it gets back to the old high, I'll sell" or "If it drops to the low, I'll buy." But these are often arbitrary.

Herd behavior: When everyone else is panicking or chasing, doing the opposite feels reckless, even when it's actually correct. The psychological pressure to move with the crowd is enormous during volatile periods.

The result: during the moments when calm decision-making would be most valuable, people are most likely to make emotional decisions.

Mini-Case: Professionals Who Design Rules Instead of Reacting

The professionals who survive multiple market cycles rarely do so by being smarter or having better information. They do it by having predetermined rules that override emotion during volatile periods.

A simple example:

Before market opens: "If the market drops X%, I will rebalance by selling bonds and buying stocks."

During the drop: The rule triggers. No deliberation. No checking headlines. No asking "is this really the bottom?" Just mechanical execution of a predetermined plan.

This sounds boring. And it is. But boring is exactly what works during volatile periods. Because boring removes the emotional component that causes mistakes.

The professionals also typically:

- Pre-define position sizes so they can't over-concentrate

- Set stop-losses in advance (not adjusting them emotionally)

- Have predetermined rebalancing schedules (not timing based on feels)

- Limit how often they check portfolios (reducing noise exposure)

None of these approaches "beat the market." But they all prevent the kinds of mistakes that markets exploit when people are emotional and uncertain.

Emotional Response vs. Structured Response

The contrast is worth naming explicitly:

| Emotional Response | Structured Response |

|---|---|

| Reacts to daily headlines and price swings | Follows predetermined rules regardless of noise |

| Recalculates strategy constantly | Executes plan, reviews only on schedule |

| Feels pressure to "do something" | Knows when to act, comfortable with doing nothing |

| Driven by recent market action | Driven by long-term plan and allocation |

| Mistakes feel real and regrettable | Mistakes are systematic, adjustable, expected |

| Volatility feels dangerous | Volatility is expected, sometimes opportunity |

| Exits on fear, enters on FOMO | Exits and enters based on plan, not emotion |

One approach treats volatility as a threat. The other treats it as terrain to navigate with a map.

Why Repeatability Matters More Than Prediction

You cannot predict markets with certainty. Professional traders know this. Successful investors know this.

What you can do is design a repeatable process that works across many different market environments.

A rule-based system doesn't need to predict whether the Fed will raise or cut rates. It just needs to respond consistently to whatever happens: "If volatility spikes above X, reduce position size. If it normalizes, return to target allocation."

The beauty of repeatability is that you don't need to be right about the specific outcome. You just need to be consistent about your response across many outcomes.

Over time, consistency compounds. Emotional reactions don't. One person following a sensible rule through 10 market cycles will outperform one person trying to predict each cycle correctly.

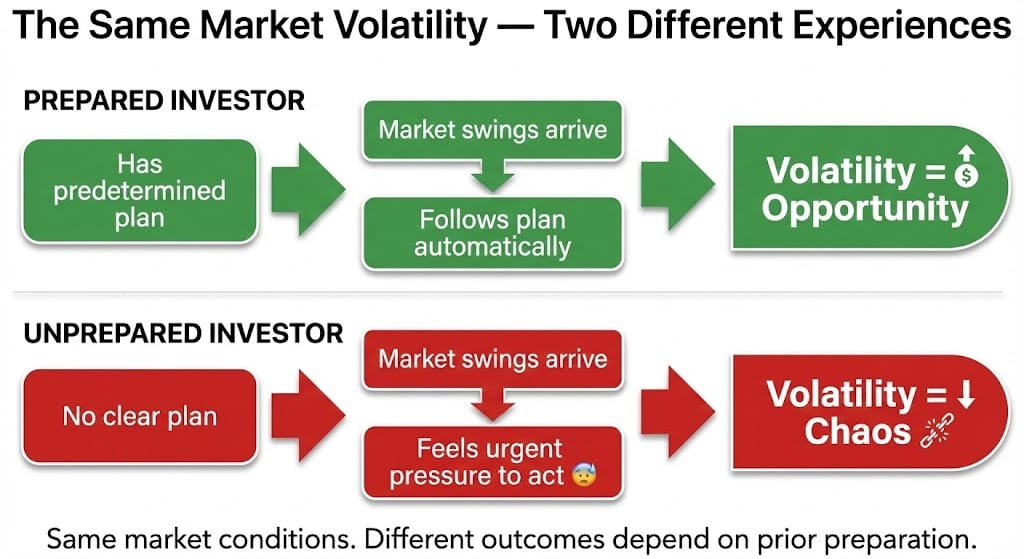

Chaos vs. Opportunity

The difference between periods that feel like chaos and periods that feel like opportunity often depends on whether you were prepared.

If you have no plan and markets start swinging wildly, it's chaos. You have no idea what to do. Every move feels reactive.

If you have a predetermined plan and markets start swinging wildly, it's an environment where your plan can be executed. You might even have opportunities to buy or rebalance according to your plan.

Same market conditions. Different experience. The difference is preparation, not luck or skill.

Protecting Time, Capital, and Mental Bandwidth

During periods of monetary contradiction and high volatility, three things get depleted quickly:

Time: You spend it checking markets, reading commentary, second-guessing decisions. That time comes from somewhere else—work, relationships, rest.

Capital: Emotional decisions during volatile periods often lead to buying high, selling low. Capital gets misallocated or lost to bad timing.

Mental bandwidth: The cognitive load of trying to navigate uncertainty is enormous. It crowds out other thinking, other decisions, other life.

A structured system protects all three by removing the need to decide constantly.

You have a plan. The plan tells you what to do in different scenarios. You don't need to keep deliberating. You execute and move on.

How Professionals Navigate Contradiction

Veteran market participants often rely on rule-based systems to navigate volatile periods. Larry Benedict, a long-time professional trader, has shared insights into how structured approaches can reduce emotional decision-making during market swings.

The appeal isn't prediction accuracy. It's systematic consistency — knowing how you'll respond before the moment of stress arrives.

Reflection — Volatility Fades, Habits Remain

Here's something worth remembering: volatility is temporary. Habits are durable.

The periods of monetary contradiction and high volatility will end. They always do. Markets will settle on a new equilibrium. Uncertainty will fade. The noise will quiet down.

But the habits you build during volatile periods remain. If you learned to panic-sell during downswings, that habit persists. If you learned to chase momentum during upswings, that habit persists. If you learned to follow a disciplined plan regardless of noise, that habit persists.

The most valuable thing you can get from a volatile period isn't profit (that's uncertain). It's proof that your system works and your discipline holds up under stress.

TSUNAMI America’s Next Financial

InvestorPlace Media

Markets don't reward people who trade most frequently. They don't reward people who call the bottoms and tops. They don't reward adrenaline or boldness or clever predictions.

Markets reward people who have a plan, stick to it, and don't let noise distract them.

During calm periods, this approach feels boring and maybe even suboptimal. But calm periods don't test your discipline. Volatile periods do.

And volatile periods—moments of monetary contradiction, conflicting signals, genuine uncertainty—are where the real advantages compound.

Not through brilliance, but through structure. Not through prediction, but through preparation. Not through excitement, but through calm, repeatable process that survives noise.

That's what separates the people who look back on volatile periods with regret from those who look back with satisfaction.

The difference isn't luck. It's whether they had a plan before the volatility arrived.

—

Claire West