Where Big Tech Buys the Boring

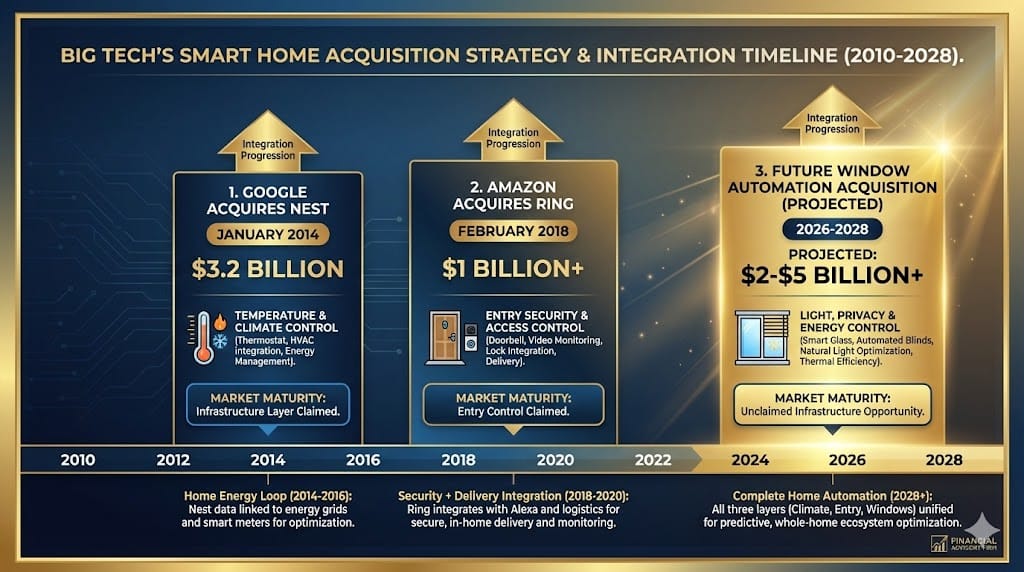

Google acquired Nest, a smart thermostat maker, for $3.2 billion in 2014. The announcement received muted enthusiasm. A thermostat—the most mundane object in the home, clicked once or twice a year—was worth more than many companies that made consumer headlines. Yet Google understood something that market attention misses: control layers are more valuable than novelty.

Four years later, Amazon bought Ring, a smart doorbell company, for over $1 billion. Again, the narrative struggled. A doorbell. Yet within a few months, Amazon had also acquired Blink, a second doorbell company, because the control layer—the entry point to the home, the integration point with delivery, the visual data stream—was strategically necessary. The doorbell was merely the hardware.

These acquisitions followed a pattern that had nothing to do with consumer excitement and everything to do with infrastructure. Big Tech buys the boring because boring is where control lives.

The pattern is now obvious in retrospect. But prospectively—while the category is fragmented, the startups are losing money, and the incumbent manufacturers are comfortable with their slower, less-automated products—the opportunity remains invisible to most observers.

Why Utility Beats Novelty

Smart home narratives fixate on robots, artificial intelligence integration, voice control. These feel innovative. The actual value in smart homes accumulates in layers that are barely noticed: thermostats that learn occupancy patterns, doorbells that authenticate visitors, locks that integrate delivery access.

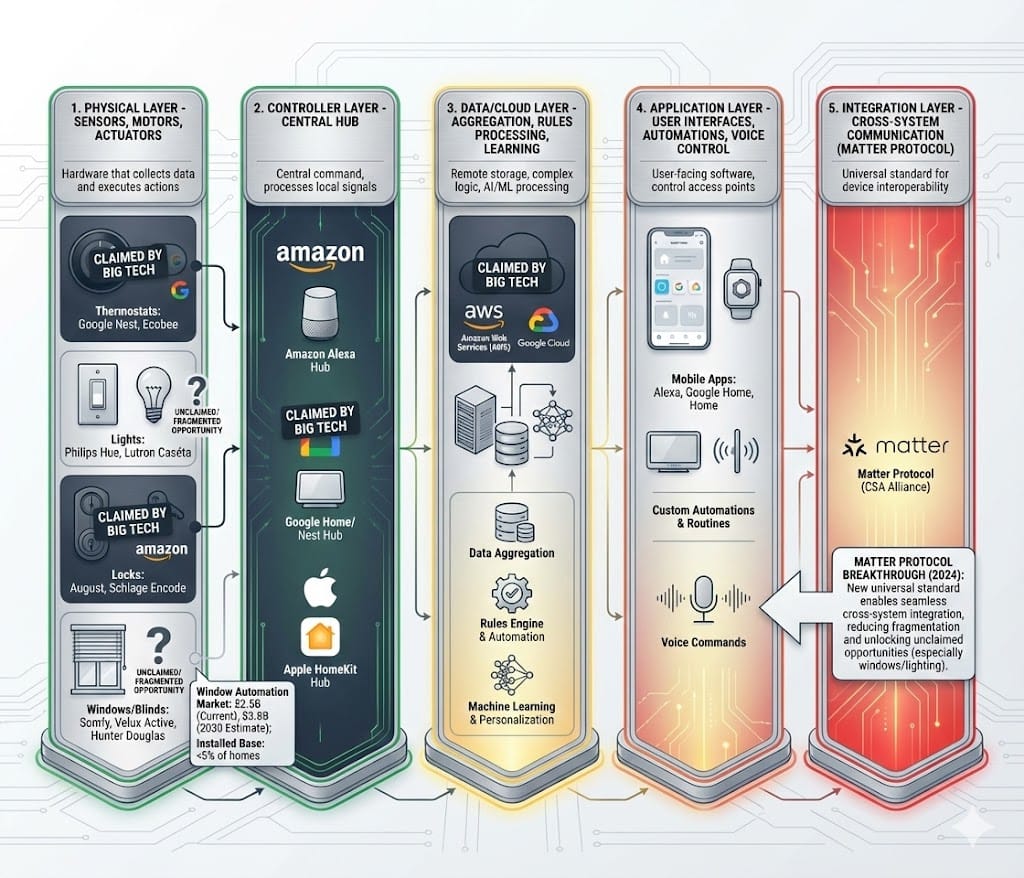

A smart thermostat controls something fundamental: energy flow through the home. It creates a feedback loop between the system (furnace, air conditioning) and data (temperature, occupancy, weather). Once that loop is established and integrated with other systems, the thermostat becomes an infrastructure node—not a gadget, but a control layer.

The same logic applied to the doorbell. Ring was not acquired because it took better video than competitors (though it did). Ring was acquired because a doorbell—the point where delivery workers, guests, strangers interact with the boundary of your home—is a control point. With integration to Amazon Key (the in-home delivery service), the doorbell became part of a logistics infrastructure layer.

Infrastructure layers are invisible until you need to integrate something else. Then they become indispensable.

Google acquired Nest for $3.2 billion.

Amazon bought Ring for over $1 billion.

Each move was a calculated bet on the future of connected living.

Now, Apple is entering the smart home war—launching Face ID-powered smart locks and in-home displays hubs. As the giants race to dominate the $158B smart home market, one critical category remains wide open… and ripe for innovation:

Smart window shades.

It’s the most boring thing in your home—and the biggest opportunity. From apartments to offices to hotels, shades cover billions of windows—and yet, not one major player has owned this space. Until now – meet RYSE.

This startup is leading the charge in smart shade automation with patented technology that works with any window shade or blind—turning it smart in minutes.

And the traction is real:

- 📍 Sold in 100+ Best Buy locations across North America

- 💡 10 granted patents protecting their IP

- 📈 Over $15M in lifetime revenue

- 🚀 200% YoY growth

Just like how Ring reinvented doorbells and Nest reimagined thermostats, RYSE is defining the future of smart shades—and could be the next prime acquisition in a trillion-dollar ecosystem.

👉 This is a rare opportunity to invest at just $2.35/share —before Big Tech next potential acquisition.

This email contains a paid advertisement for the Ryse Regulation A+ offering. Please review the offering circular at https://invest.helloryse.com/

The Unclaimed Layer: Windows

The pattern established by Nest (2014) and Ring (2018) should have indicated where Big Tech would move next. A thermostat controls temperature. A doorbell controls entry. What controls light, privacy, energy flow, and occupancy signals simultaneously?

Windows.

Window automation is the most significant smart home category that remains unclaimed by Big Tech. The market is $2.5 billion today, growing to $3.8 billion by 2030. Hunter Douglas, Lutron Electronics, Legrand—traditional manufacturers—still dominate, with software that moves slowly and ecosystems that integrate poorly with Alexa or Google Home.

Meanwhile, startups like RYSE have captured a completely different angle: retrofit solutions that attach to existing blinds, require no replacement, and integrate with smart home ecosystems. This is not accidental product design. This is infrastructure thinking.

Why windows? Because a window automation system controls multiple data streams simultaneously. Light levels (brightness, glare, natural illumination). Temperature (heat gain through unshaded glass; passive solar). Privacy (occupancy simulation, presence indication). Energy consumption (windows represent 30 percent of home heating and cooling losses).

When windows are connected—when they integrate with lighting systems, thermostats, security systems, weather forecasts, occupancy sensors—they become a control layer that touches virtually every other smart home subsystem.

But today, most windows remain dumb. They are controlled (if at all) by manual pull cords or old remote controls. The startups introducing smart window automation are still positioning it as a convenience. The infrastructure opportunity—windows as a data collection and control point for the entire home's energy, privacy, and comfort systems—remains largely unarticulated.

This is the gap where acquisition opportunity lives.

Pattern Recognition: Boring, Fragmented, Then Inevitable

The acquisitions follow a consistent pattern that repeats:

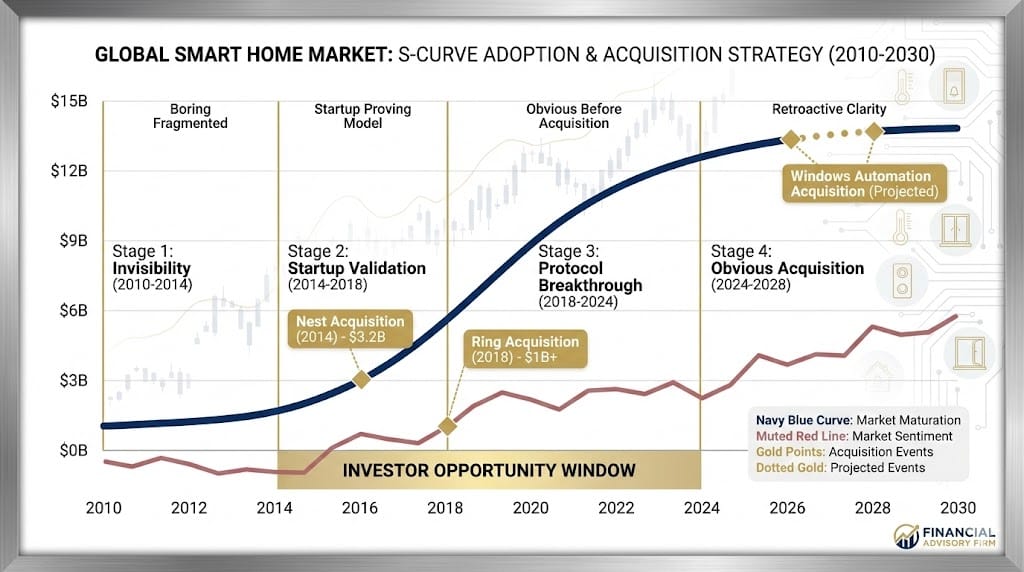

Stage 1: Invisibility. The category exists but feels unglamorous. Window coverings are "treatments," not infrastructure. Nobody writes venture capital theses about blinds. The market is fragmented across dozens of suppliers. Growth is steady but unexciting.

Stage 2: Startup Validation. A few startups—RYSE, others—begin solving specific problems: retrofit ease, smart home integration, energy scheduling. These startups are not trying to replace the entire window covering industry. They are automating what already exists.

Stage 3: Protocol Breakthrough. The Matter protocol (launched 2024) finally enables interoperability across ecosystems, removing the proprietary barrier that prevented integration. Suddenly, a window automation device can communicate with lighting, HVAC, and security without special bridges.

Stage 4: The Obvious Acquisition. Once startups have validated the market, proven the product works, integrated with major ecosystems, and begun showing unit economics, Big Tech acquires. The acquisition is announced as strategic—connecting the home's energy management, security, and automation—but the market had been ignoring the opportunity for years.

This is exactly what happened with Nest (validated by 2014, then obvious when Google acquired it). This is exactly what happened with Ring (validated by 2017, obvious by 2018 acquisition).

The window automation market is approximately at Stage 3: protocol breakthrough beginning to enable broad integration, startups proving out the model, but no Big Tech acquisition yet. This is the phase that appears to observers as "boring fragmentation." It is actually the calm before structural inevitability.

Exciting Tech vs. Embedded Tech

| Dimension | Exciting Tech | Embedded Infrastructure |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer Perception | Novel, innovative, "wow" factor | Invisible, utility, background |

| Market Narrative | "Disruption," AI, quantum computing | "Control layer," efficiency, integration |

| Adoption Speed | Fast initial buzz, then plateau | Slow adoption, then exponential (once integrated) |

| Incumbent Response | Quick competition, price wars | Slow movement (protecting legacy revenue) |

| Startup Visibility | High (can raise capital on narrative) | Low (narrative struggles; capital harder to raise) |

| Acquisition Timing | Often after hype cycle fades | After market validation, before dominance |

| Integration Value | Standalone, limited synergy | Multiplies value across entire ecosystem |

| Real Strategic Value | Lower than perceived | Higher than perceived |

| Valuation Multiple | Premium paid for narrative | Bargain on fundamentals, then repriced post-acquisition |

| Retrofit Compatibility | Often not applicable | Often critical to adoption (existing homes) |

| Matter Protocol Enablement | Less relevant | Transformative (removes integration barriers) |

The pattern is consistent: exciting tech gets venture capital and media coverage. Embedded infrastructure gets overlooked until acquisition proves its strategic necessity.

Why Incumbents Wait

Traditional window covering manufacturers—Lutron, Hunter Douglas, Legrand—could automate their products today. They have manufacturing, distribution, customer relationships. Yet they move slowly because:

- Revenue Structure: Replacement blinds are higher revenue per unit than retrofit devices. Motorized replacement is higher margin than adding motors to existing blinds. Incumbents optimize for their existing channel.

- Validation: Incumbents prefer startups to validate market demand first. Let small companies invest in cloud infrastructure, software, Matter integration. Acquire when product-market fit is proven.

- Ecosystem Threat: Once a startup shows the retrofit model works, Big Tech must act quickly. If Google doesn't acquire the window automation leader, Amazon might. This creates acquisition pressure at the moment the market reaches critical mass.

This is why Window automation startups exist in a compressed timeline. They have perhaps 3-5 years before Big Tech decides this layer is strategically necessary, before an acquisition happens, before the market reprices.

During those years, the narrative remains: "boring fragmented market." The opportunities remain quiet, invisible, mostly ignored.

Why Compatibility Beats Reinvention

The critical insight that separates winners from losers in infrastructure layers is compatibility. RYSE does not try to replace existing blinds. It attaches to existing blinds and adds automation. This sounds like a technical difference. It is actually a strategic one.

Replacement products require:

- Consumer to remove old blinds

- Electricians to rewire homes or use batteries

- Higher price point

- Slower adoption in retrofit market (existing homes dominate)

Retrofit products require:

- Clipping or attaching to existing blinds

- No rewiring

- Lower price point

- Faster adoption (easier for existing homes)

The installed base of windows in existing homes is massive. Billions of windows, all with existing coverings. A retrofit solution that works with what is already there has fundamentally better adoption dynamics than a replacement solution, even if the replacement is technically superior.

This is why startups often spot the opportunity before incumbents. Incumbents are designed for replacement (higher revenue). Startups optimize for retrofit (faster adoption, larger addressable market).

The Window Acquisition Timeline

The acquisition pattern suggests a timeline. Nest (thermostat) in 2014. Ring (doorbell) in 2018. Window automation acquisition likely in 2026-2028, once market maturation reaches critical mass.

The Signal of acquisition will not come from consumer excitement (the market will still look "boring"). It will come from Big Tech recognizing that windows are the remaining control layer that integrates with energy management, security, privacy, and AI learning across the entire home ecosystem.

The valuation at acquisition will look expensive to observers not tracking the category. Just like Nest at $3.2 billion for a thermostat company. Just like Ring at $1 billion for a doorbell company. The premium is not for the product. It is for the infrastructure layer and the ecosystem integration that follows.

By the time the acquisition is announced, the opportunity will be obvious. By the time it is obvious, the early investors in the category will have compounded their capital across years of quiet, unglamorous development.

The smart home future is not being built in conversations about AI or voice control. It is being built in boring infrastructure layers that consolidate control points. Windows are next. Not because they are exciting. Because they are inevitable.

—

Claire West